Sanatorium

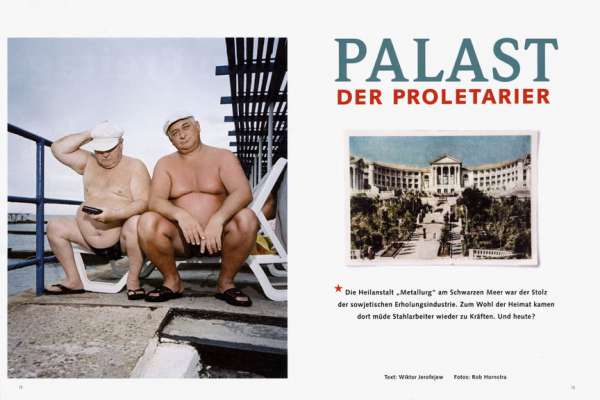

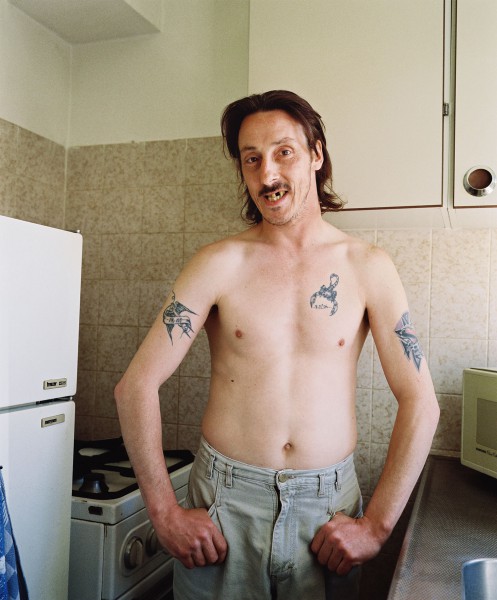

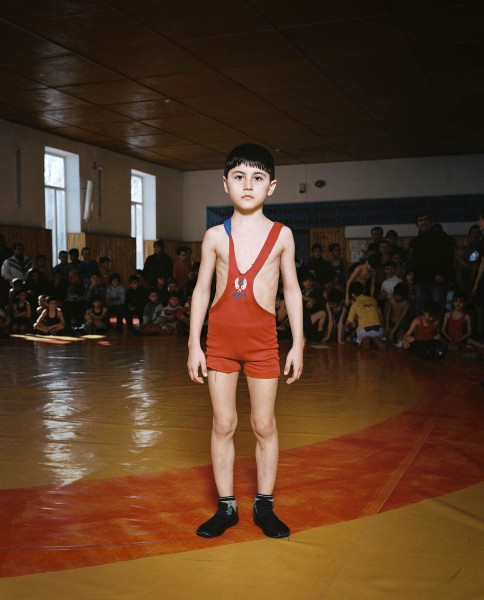

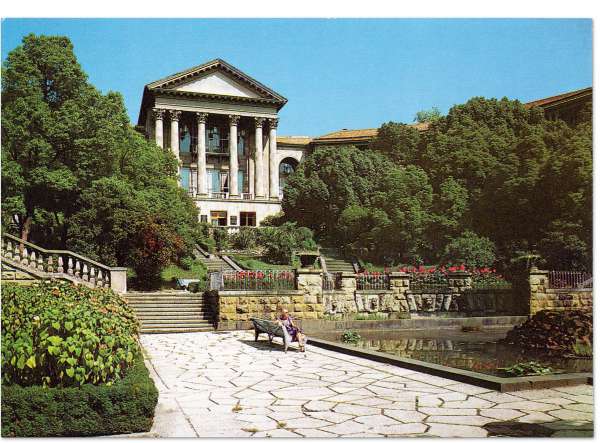

On Lenin’s orders the subtropical Black Sea resort of Sochi was opened up to the masses in the 1920s. Ministries, army units, unions and factories started to build spas and accommodation for workers, with trips being offered as a reward for hard work. The resorts also became a refuge for the Soviet elite, including politicians, cosmonauts and actors. In Soviet times, millions of workers were sent to sanatoriums in Sochi to revive their spirits and strengthen their bodies. In the run-up to the Winter Olympics in 2014, almost all the sanatoria would be converted into luxury hotels. There is no place for sentimentality when it comes to the past.

Together with writer Arnold van Bruggen I spent ten days at Sochi’s Sanatorium Metallurg, among the elderly and infirm Russians who still flock there for daily massages and 20-minute radon baths.

Sanatorium Metallurg on a postcard from 1980s

“Following Lenin’s decree in 1919 that ‘localities with curative properties are the property of the people and are to be used for curative purposes,’ Sochi has harnessed its 90 miles of spectacular coast to this end.”

View from the garden on new apartment block

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

“Before the revolution, there were 36 spas and 56 sanatoria. Today there are 350 spas and nearly 2500 sanatoria where, last year, four and a half million people were treated.”

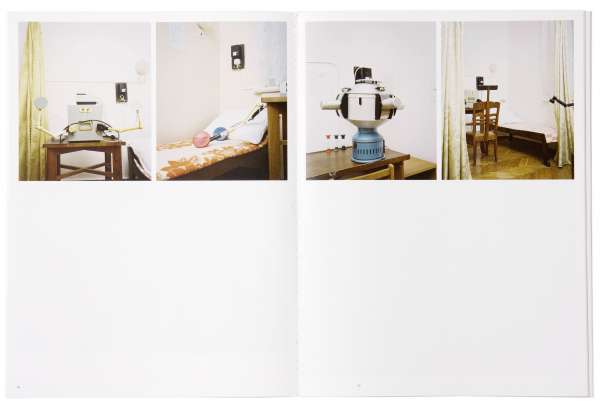

Magnetically charged sulfurous clay treatment

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

Former theater, now closed for renovation

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

“The popularity of the spas seems to be in the Soviet character. There is something about treatment based on mineral springs, sun and air that appeal to a proclivity among Russian for folk cures, natural medicines and selfdiagnoses.”

View from balcony on the Black Sea

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

“Russians often profess astonishment that Americans do not share their faith in sulfurous muds and radioactive springs.”

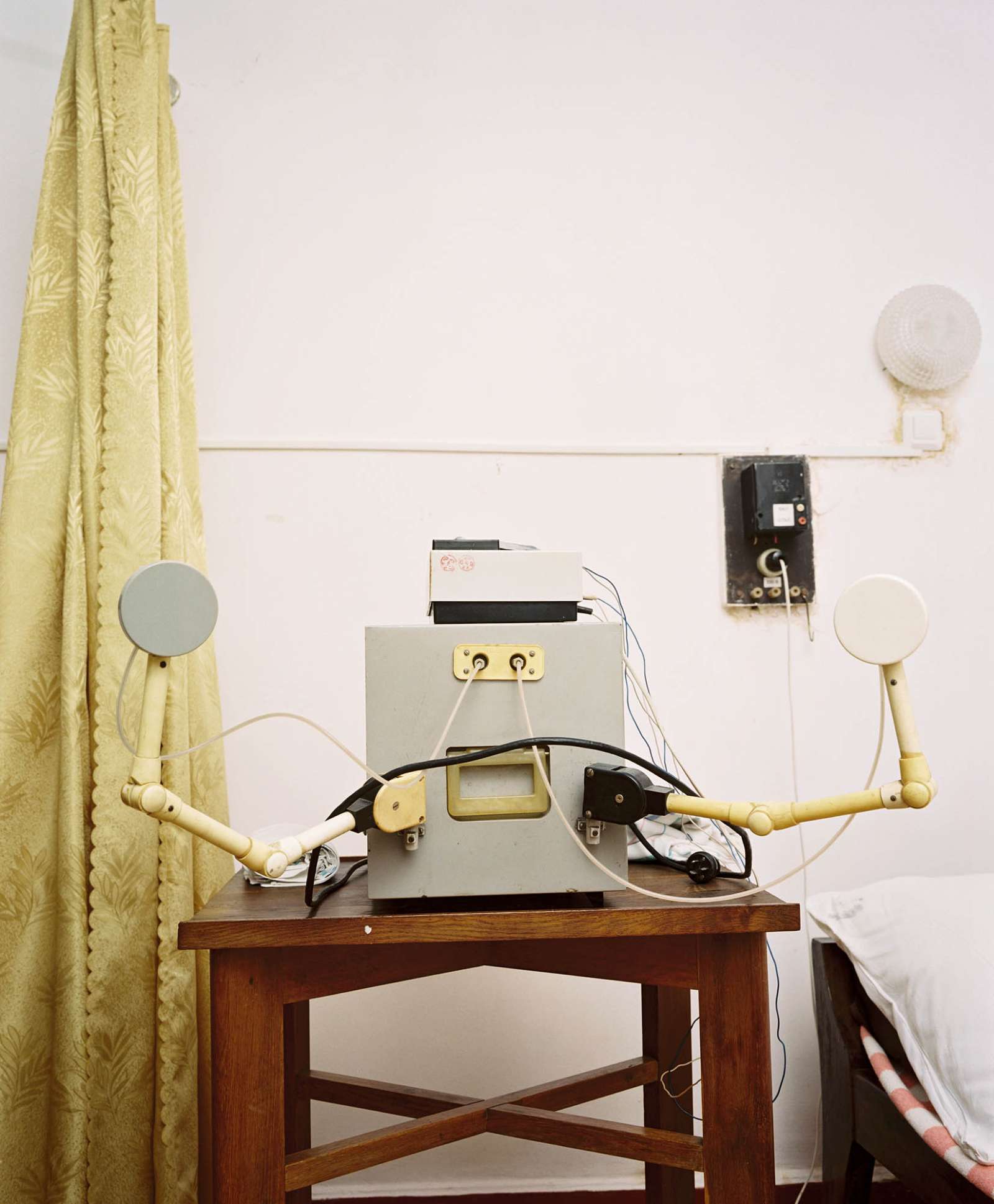

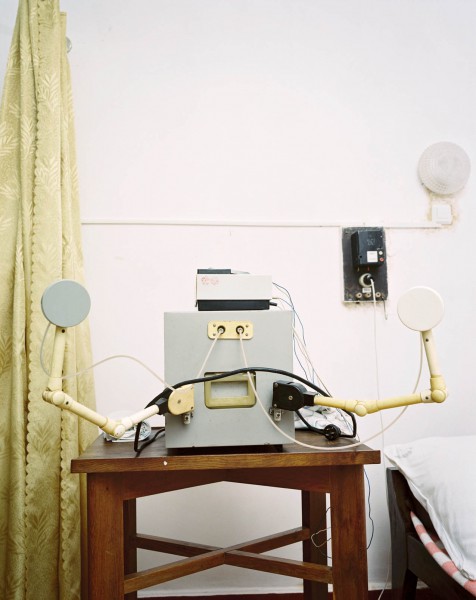

Room for radiographic treatment

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

“Like everywhere else, the hot water didn’t work, the washstands had no stoppers, the bathtubs were rusted, tiles were missing in the floors, panes of glass were broken and the toilet sputtered all day long.”

Disco night from 8 until 10 pm.

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

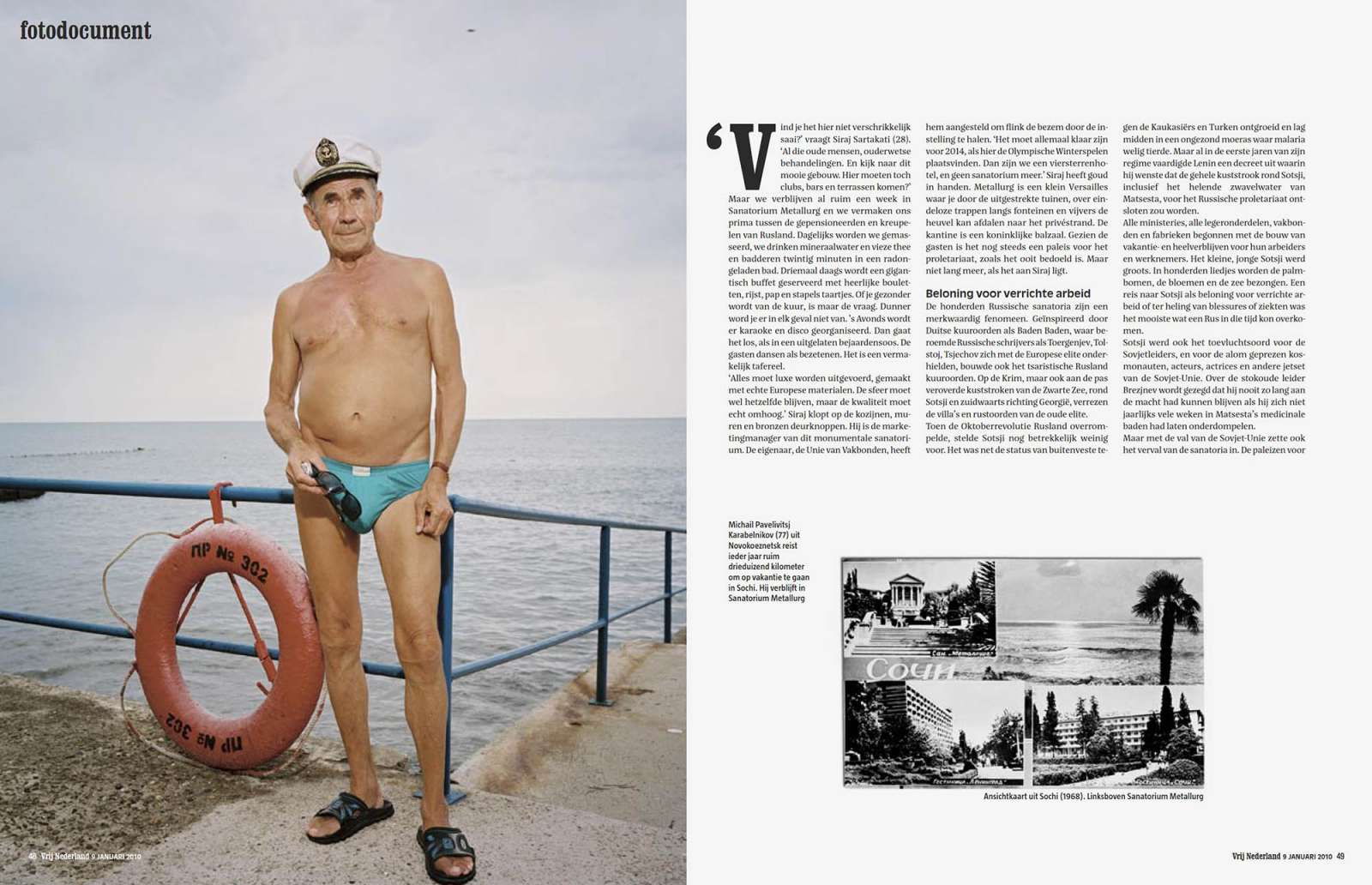

Mikhail Karabelnikov from Murmansk

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

Almost all sanatoriums have a private beach

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

“One may swim, go out in a motorboat and join excursion groups under the aegis of a hostess. But at 10 p.m., everyone must go to sleep. Only high officials and officers are exempt from this rule.”

Sanatorium Metallurg (top left) on a postcard from 1968

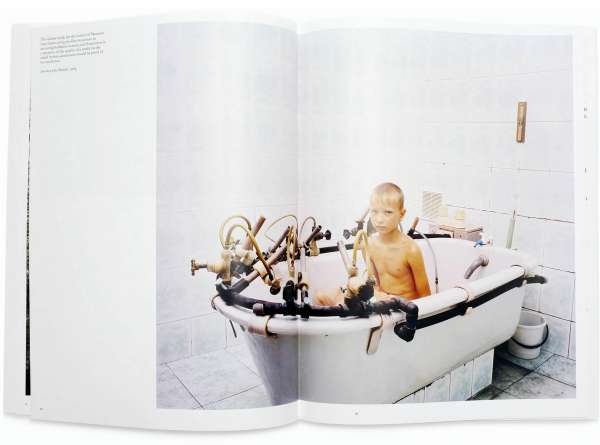

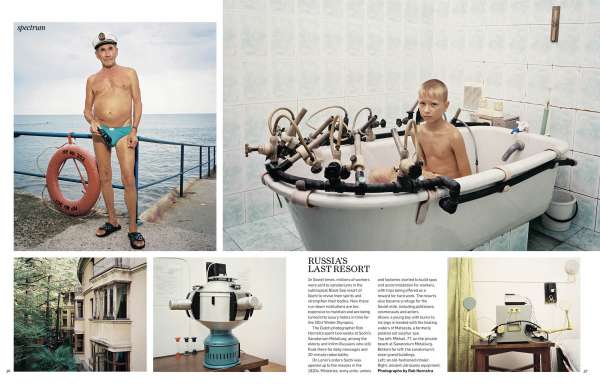

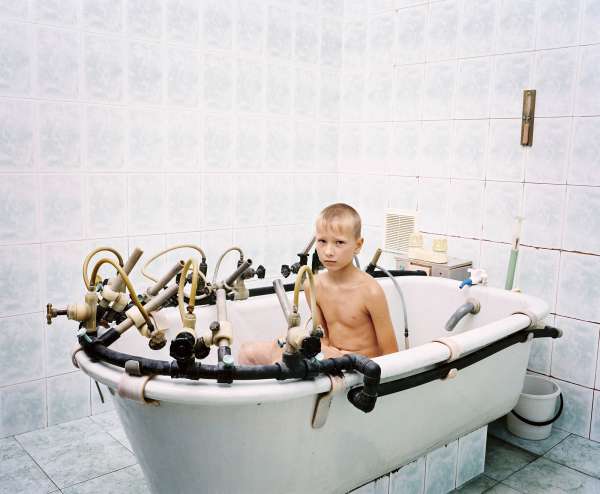

Dima gets treatment for his burns

Matsesta, Sochi, 2009

“The claims made for the waters of Matsesta vary from curing sterility in women to arresting baldness in men, and if nastiness is a measure of the quality of a medicine the smell in this sanatorium should be proof of its excellence.”

Heated saltwater pool for winter

Sanatorium Metallurg, Sochi, 2009

Introduction movie © Arnold van Bruggen, Prospektor, 2009.