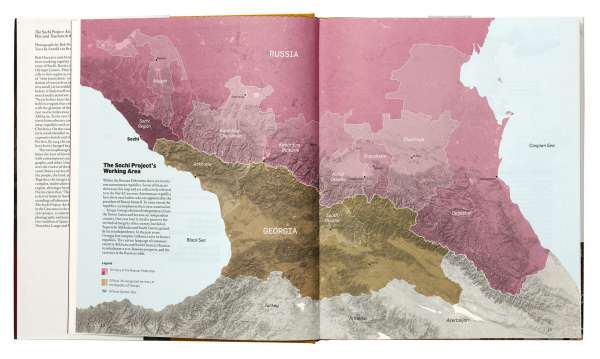

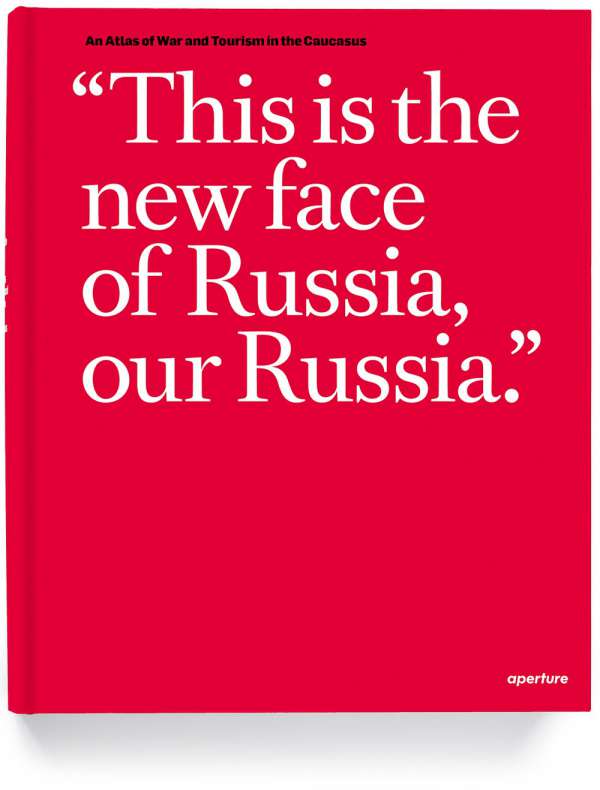

The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus

An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus delves into the complexities of the region around Sochi, Russia, and its remarkable transition in preparation to host the 2014 Olympic Winter Games. As a place where beach-tourism abuts terrorism, corruption, and poverty, it is full of contradictions. An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus draws viewers into the story of Sochi and the Caucasus, focusing on evocative individual narratives that collectively chronicle larger issues.

Recipient of the Dutch Doc Photo Award; Dutch Design Award; and Canon Prize for Innovative Photojournalism, 2014.

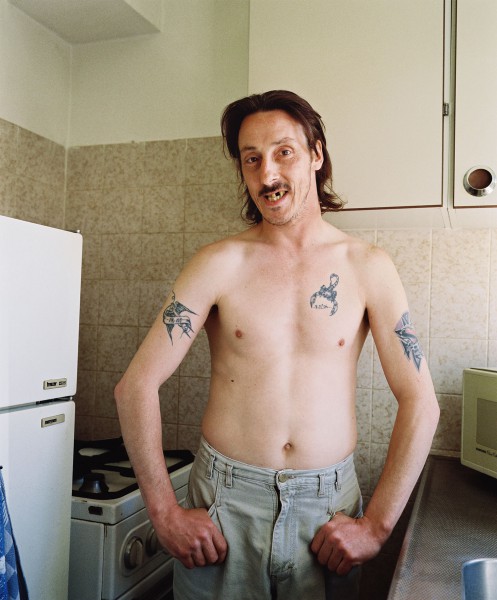

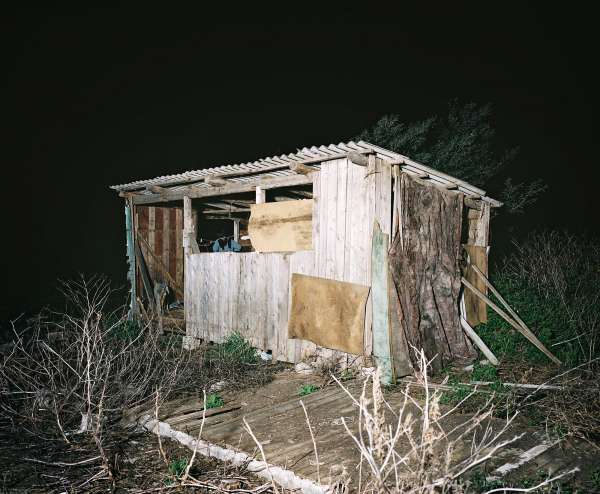

Improvised accommodation of fired Olympic site laborer Ivan, 2010.

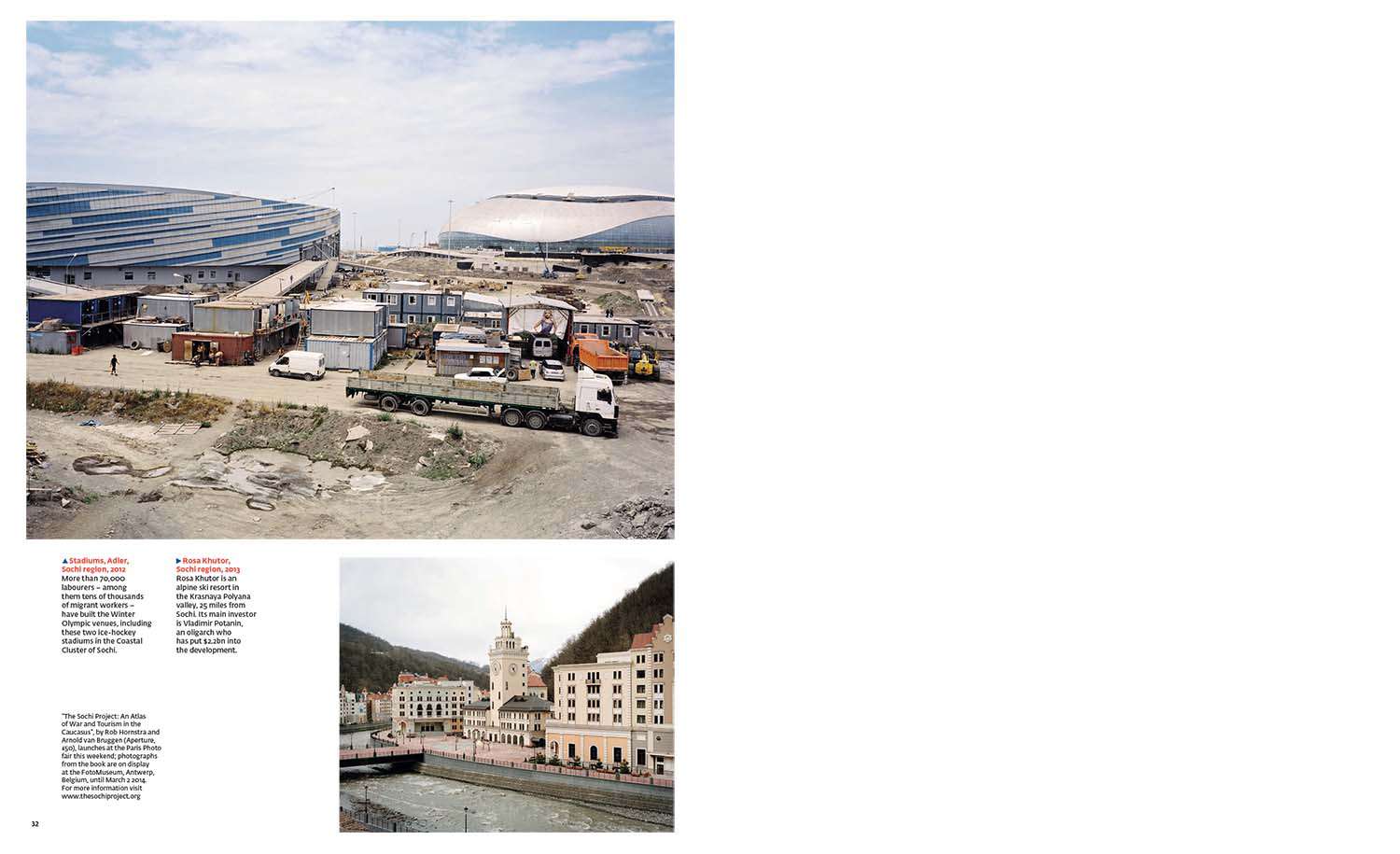

Almost finished Olympic mountain cluster in 2013.

“The Olympic family is going to feel at home in Sochi.”

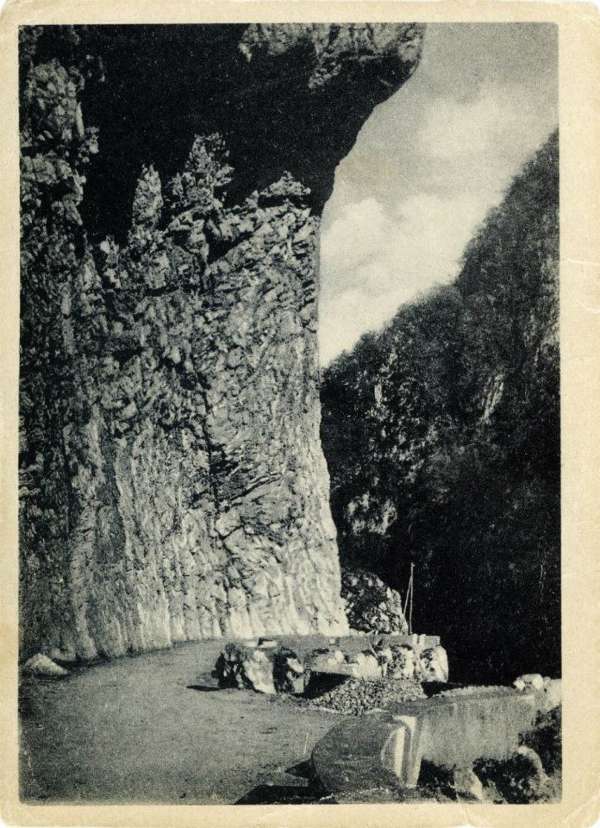

Postcard from 1930s of the now most expensive road in the world from Sochi to Krasnaya Polyana.

“It’s not that I’m against these Games. It’s the way in which they’re being realized. Krasnaya Polyana was turned into a rubbish dump. Historical monuments are being destroyed.”

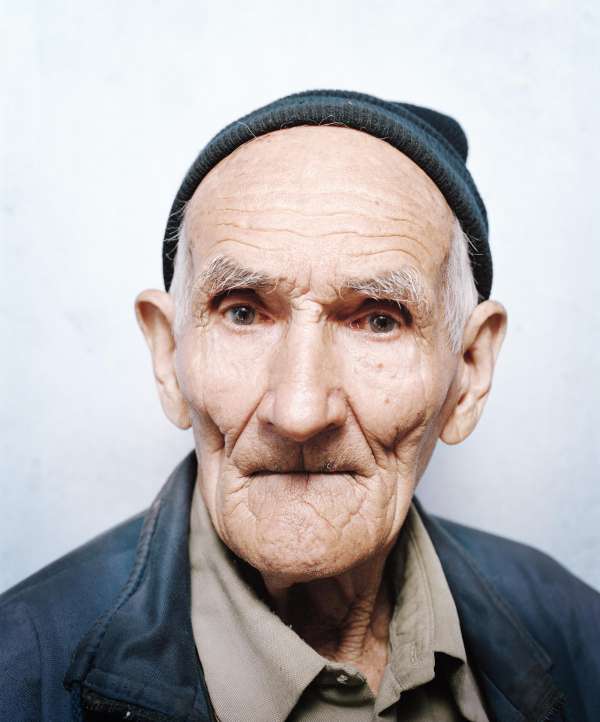

Gennadi Kuk in his hometown Krasnaya Polyana in 2010.

Katya Primakova and protesters in Sochi, 2009.

“Putin looked and looked, and then he found it: the only place in Russia without any snow, to organize the Winter Games.”

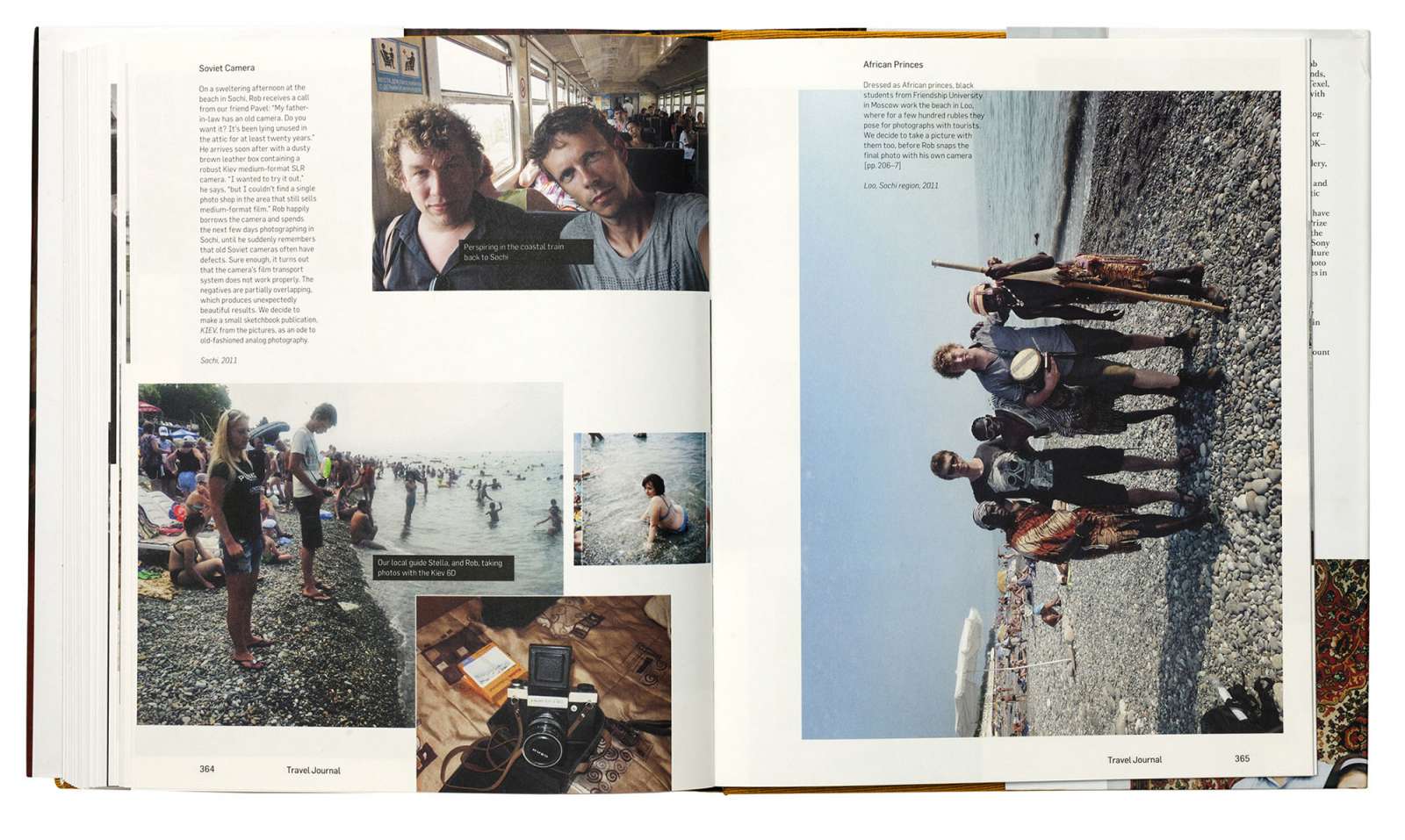

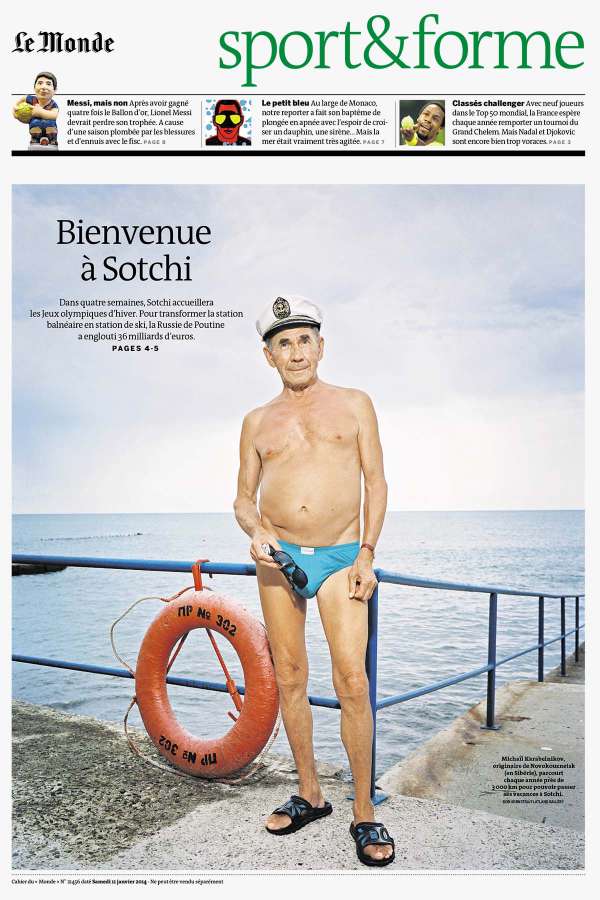

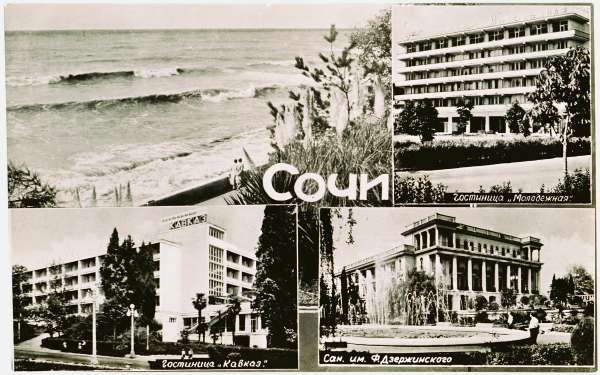

Sochi

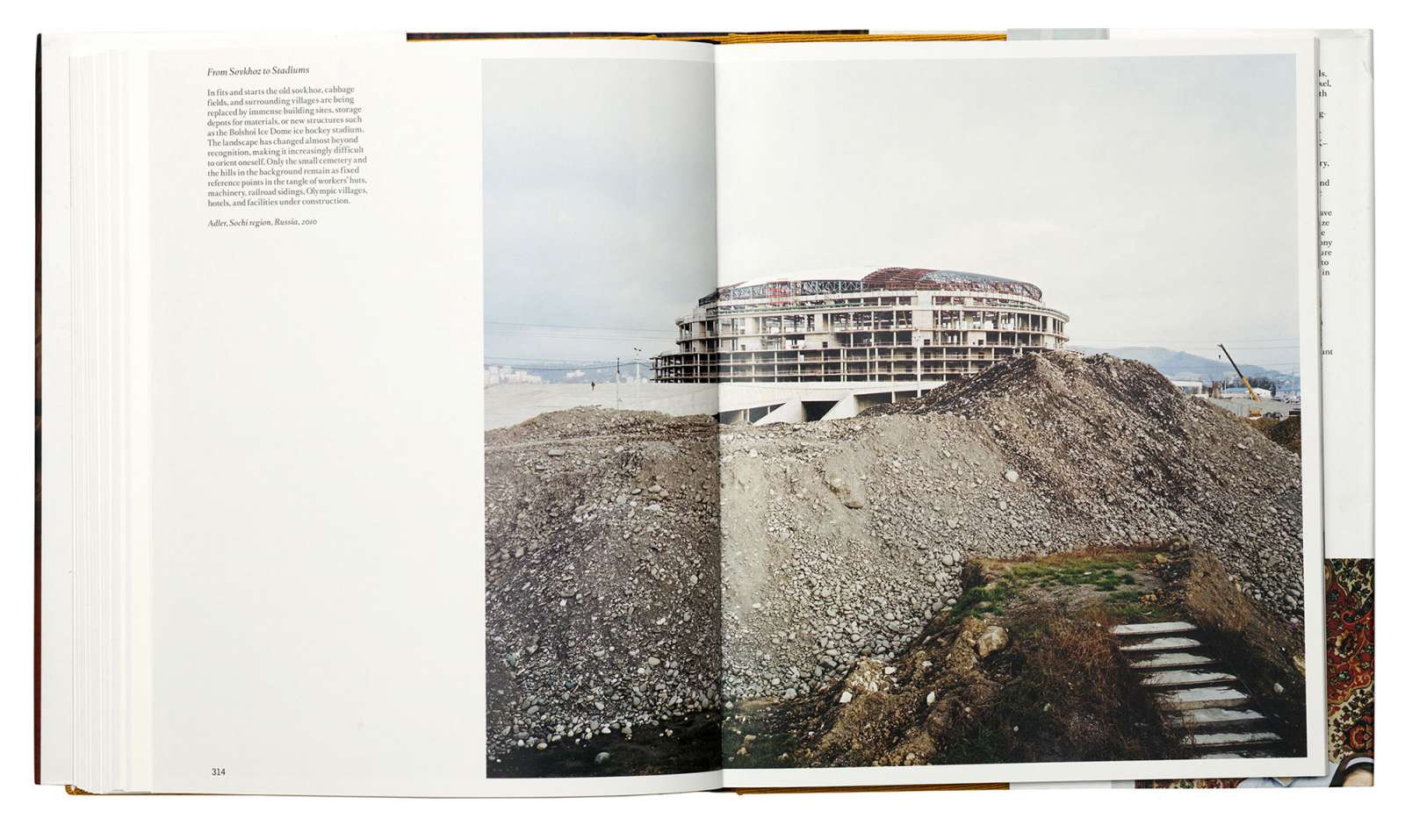

Sochi is Russia’s Costa del Sol, but even cheaper. It is famous for its subtropical climate, hotels, and sanatoria. People from across the former Soviet Union associate the coastal resort with beach holidays and first loves. The smell of sunscreen, sweat, alcohol, and roasting meat pervades the air. The sentimental music is deafening. Like any resort, Sochi has traditionally been deserted in the winter. That has all changed. To accommodate the Olympics, the city was turned upside down. The existing facilities did not meet the standards of the International Olympic Committee and the entire Olympics infrastructure had to be built from scratch: airports, commercial ports, motorways, tunnels, ski resorts, ice rinks, hotels, and villages. A budget of $12 billion was initially set aside for the enormous operation, but the final cost is estimated at $50 billion, around half of which disappeared into the pockets of contractors and subcontractors. With the Games completed, the city is intended to be Russia’s new sports and conference capital.

Hotel Zhemchuzhina (meaning ‘pearl’) on Sochi’s beachfront, 2011.

Natalia Shorogova, floor lady 2nd floor in hotel Zhemchuzhina, 2011.

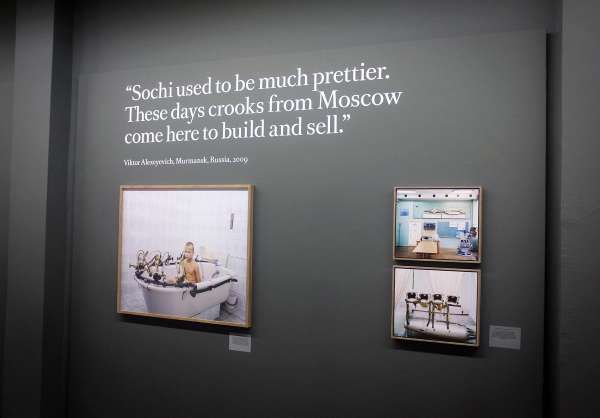

“Sochi used to be much prettier. These days crooks from Moscow come here to build and sell.”

Soviet postcard from 1968 with tourist highlights from Sochi.

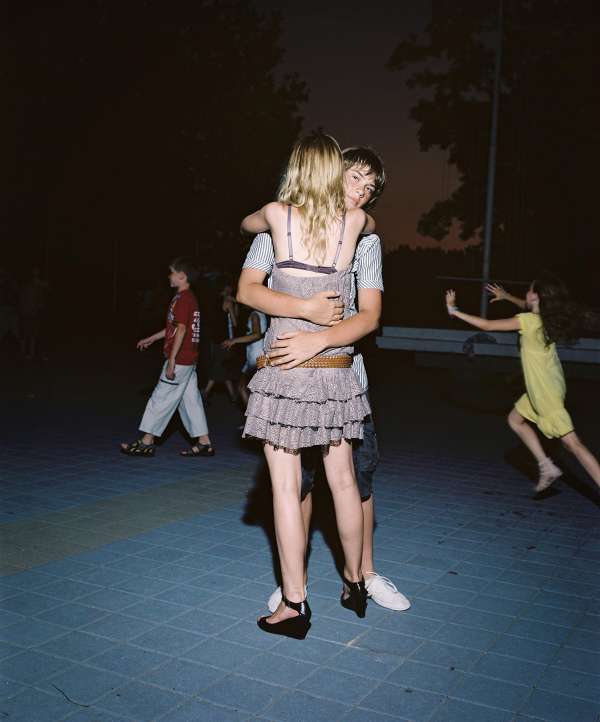

Dance floor of children’s camp Orlyonok, 2011

“The Olympic Games in the subtropics—it’s a fraud!”

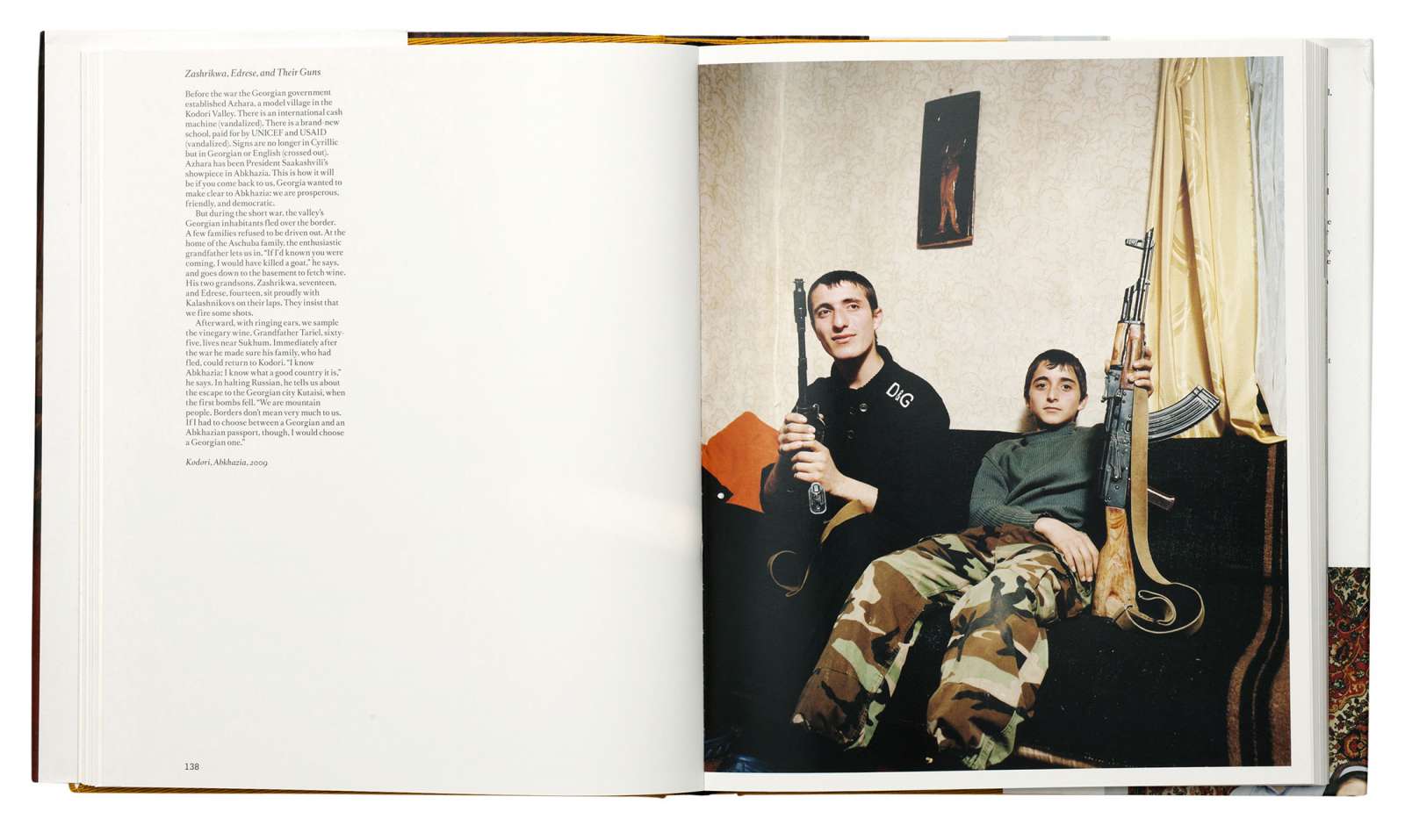

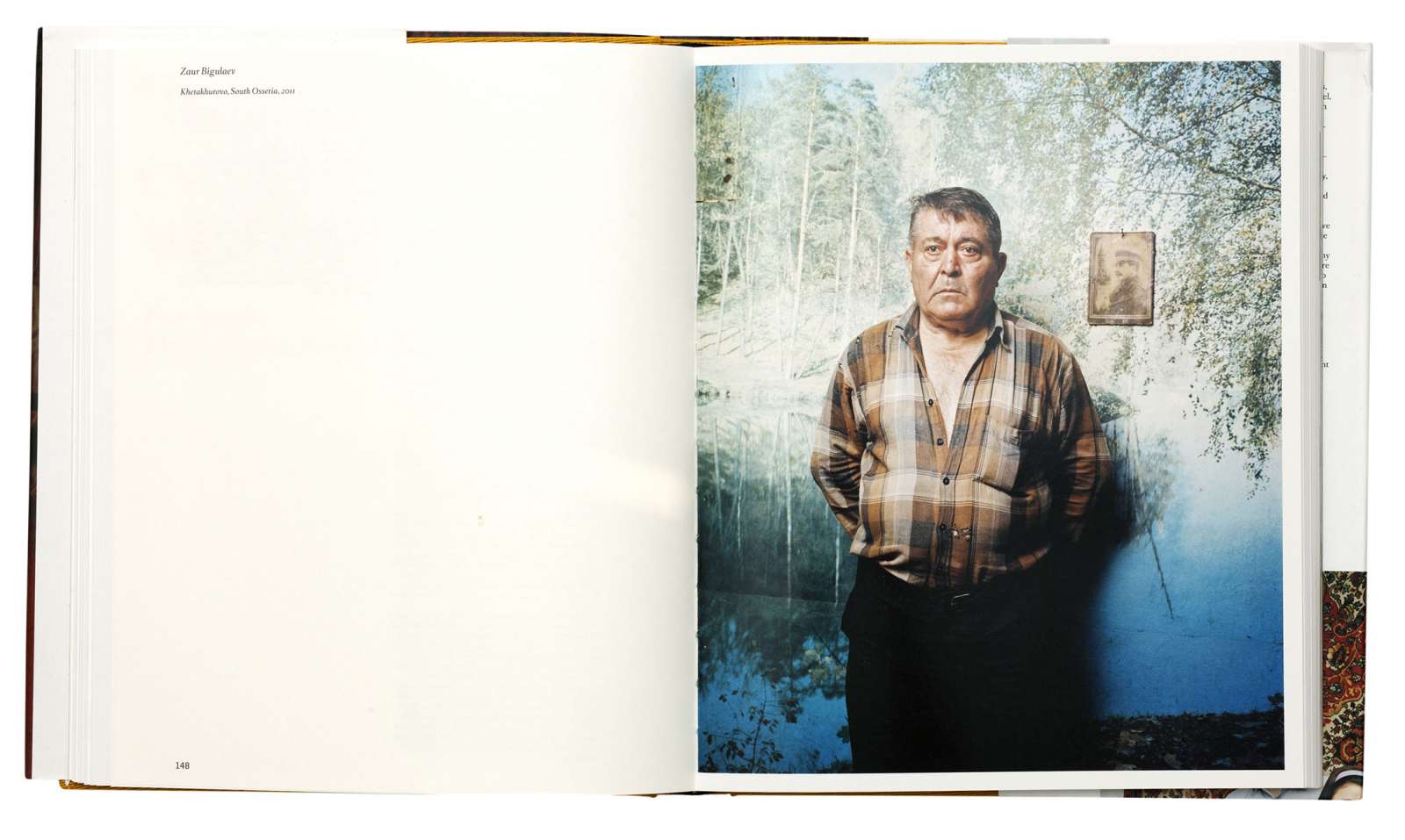

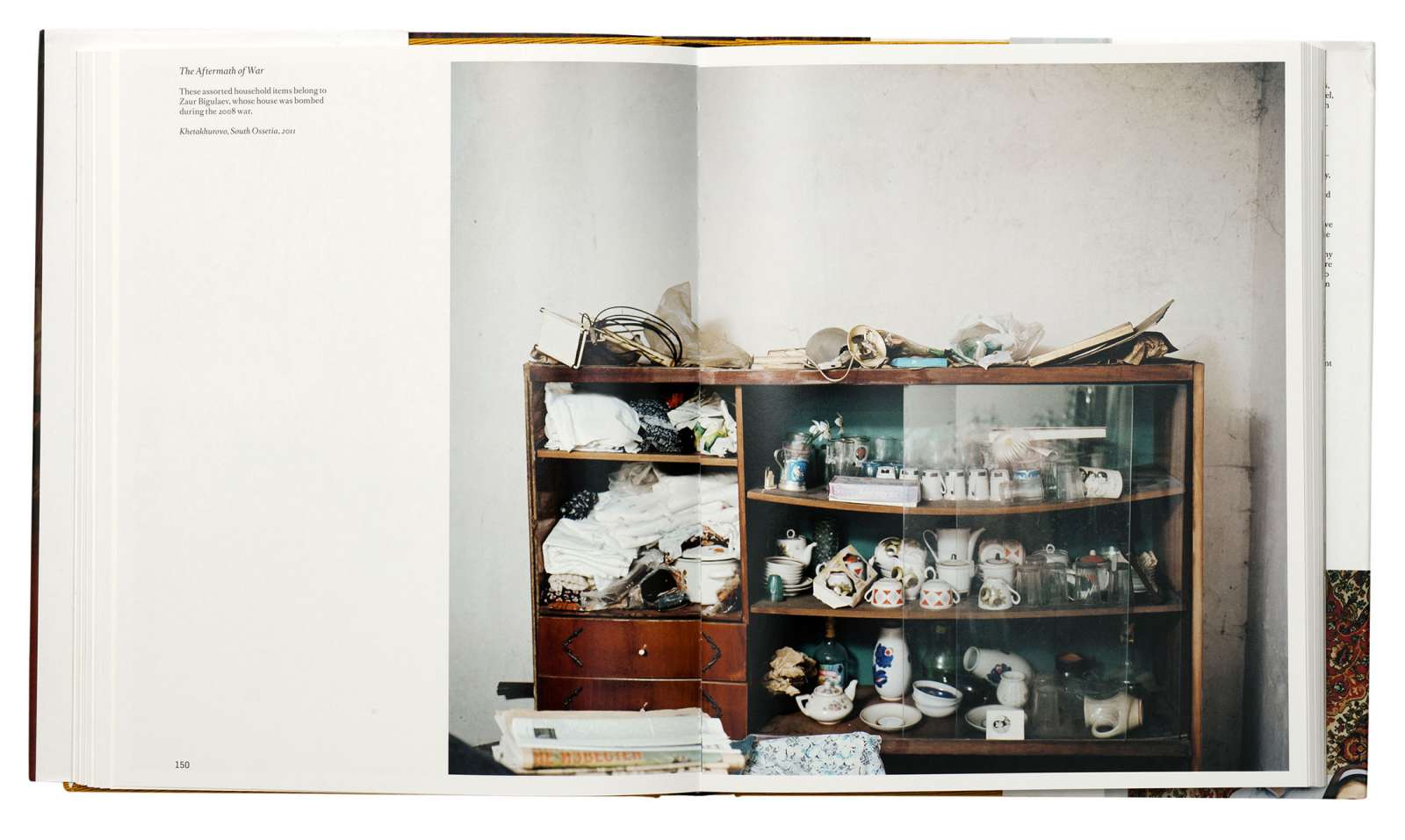

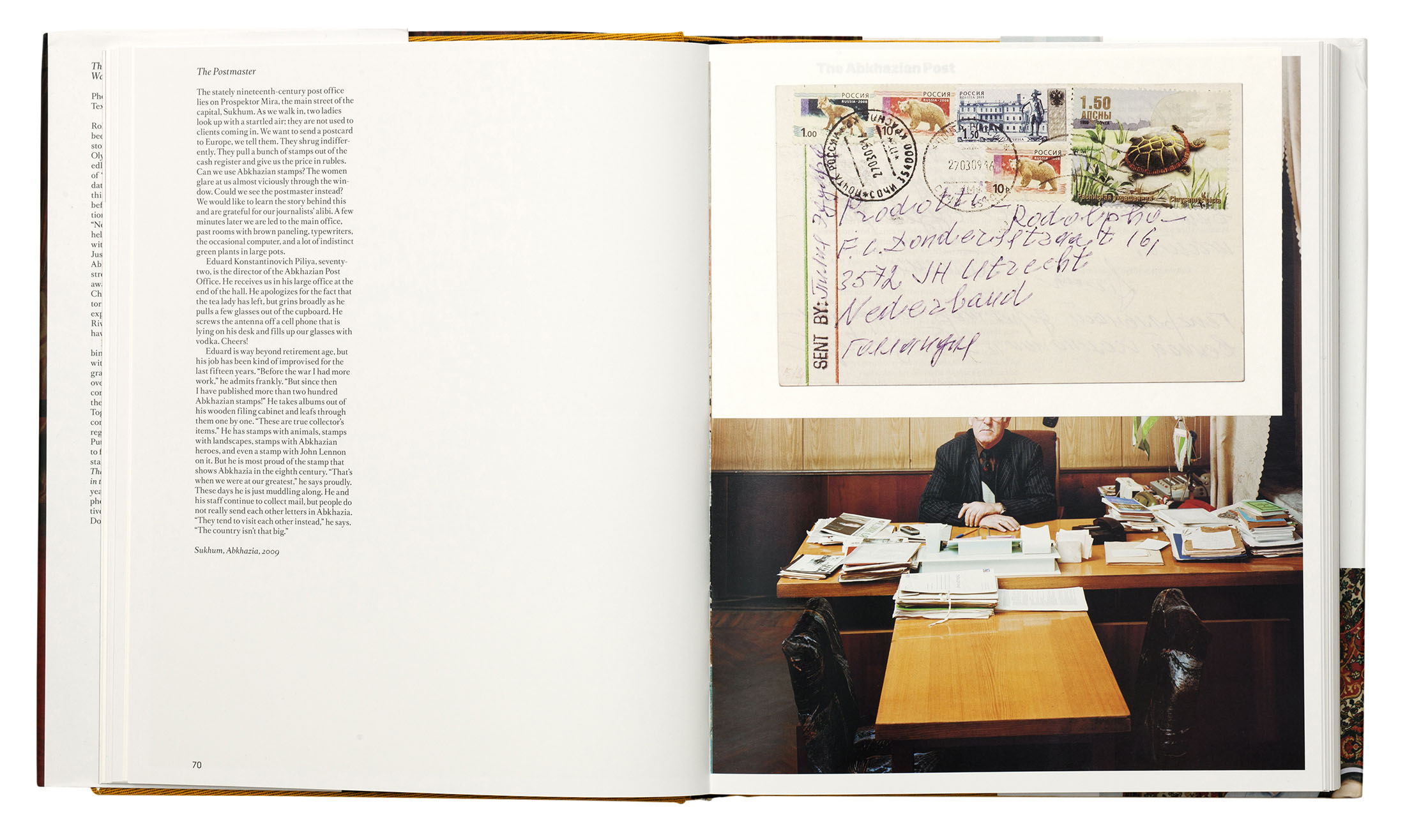

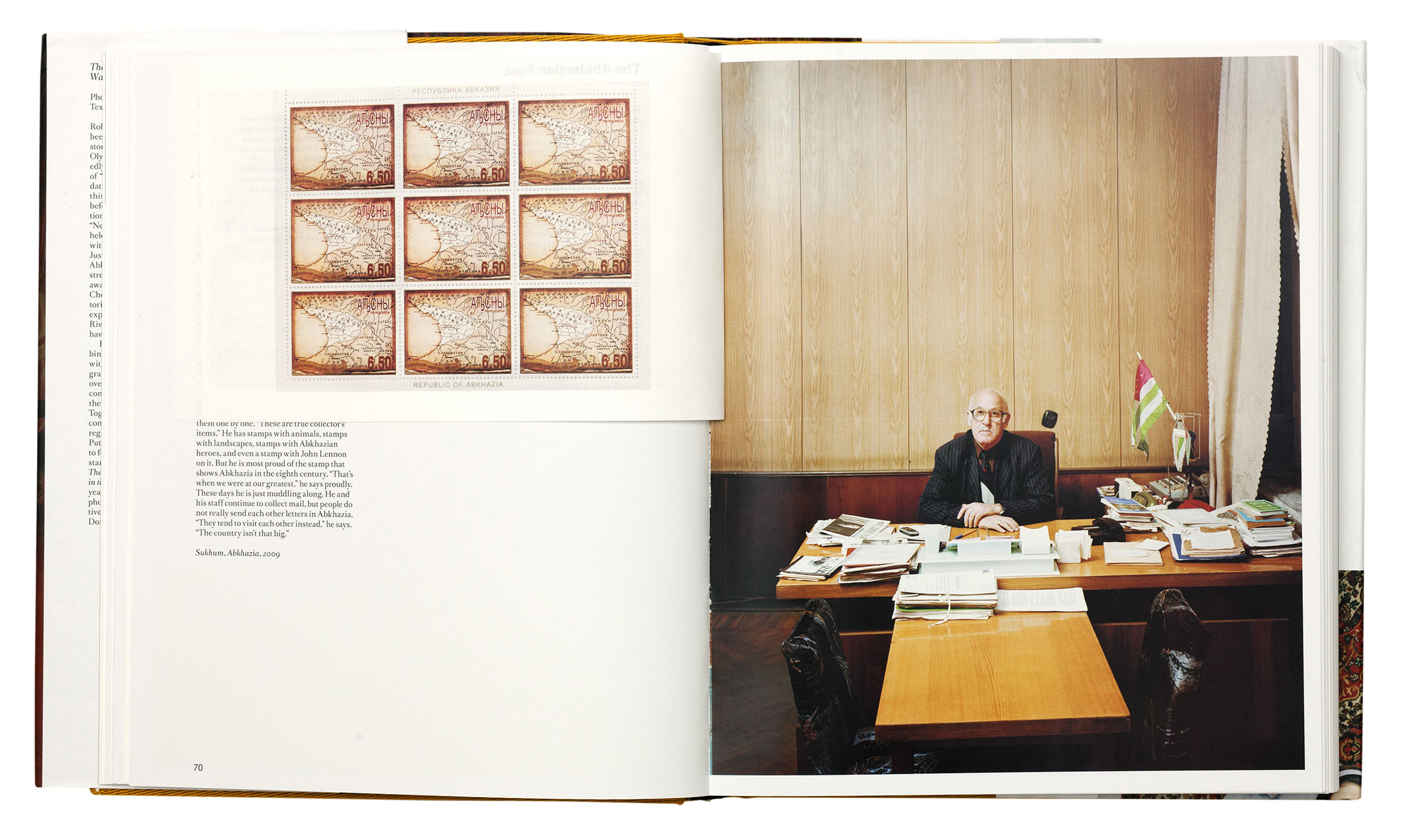

Abkhazia

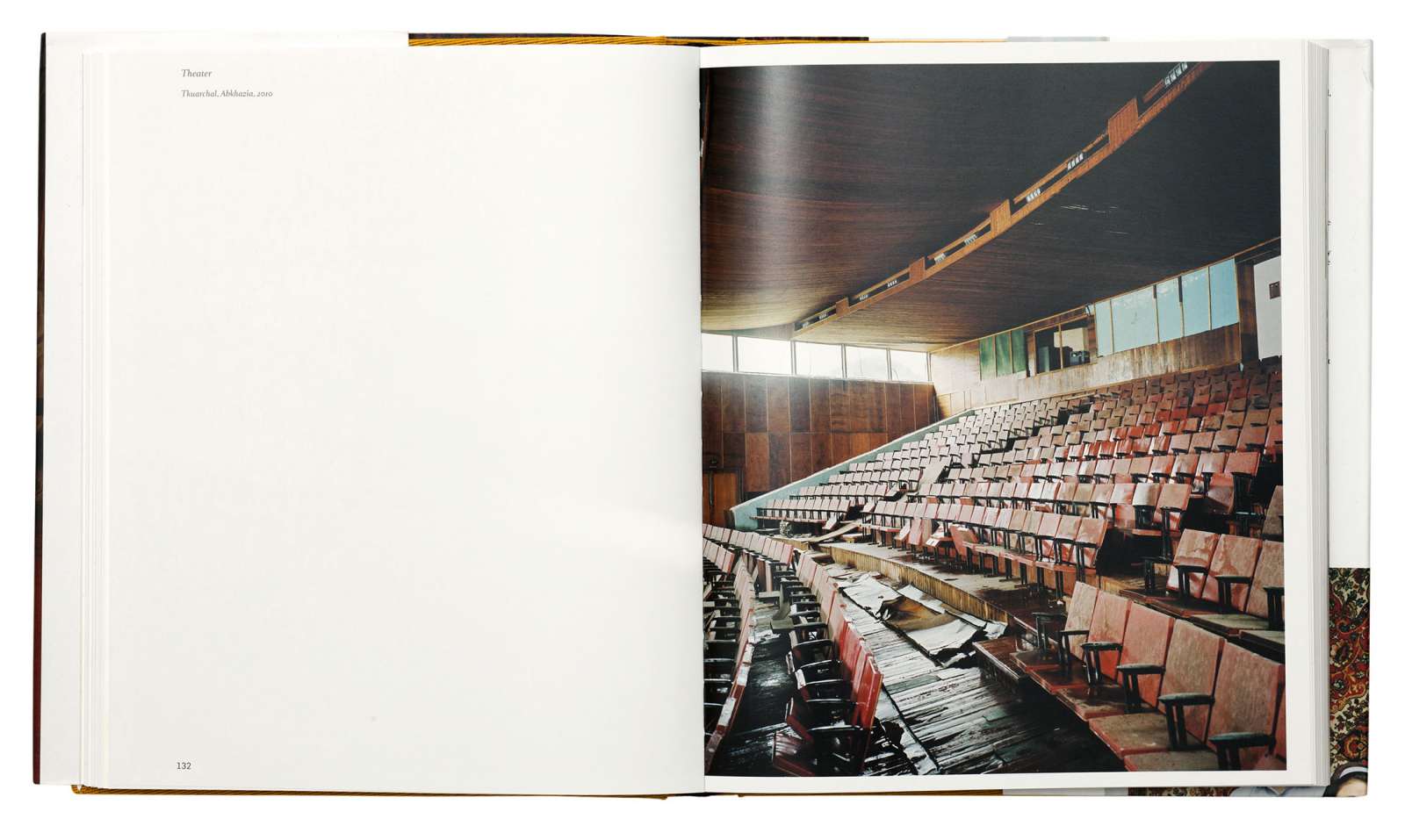

Less than five kilometers from the site of the 2014 Winter Olympics is the small country of Abkhazia, once part of Georgia. Abkhazia is a land of tea plantations and mandarin trees, a subtropical paradise where Stalin, Beria, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev once owned country houses. In 1993, a bloody civil war broke out between the Georgians and Abkhazians and more than 200,000 people fled. Many Georgian refugees still live in appalling conditions in Georgia, and Abkhazia stands empty and ruined. Only in 2008 was it officially recognized by a curious combination of nations: Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Tuvalu, Nauru, and Vanuatu. Despite official independence, Abkhazia remains impoverished. Economic developments benefit only a small elite. Peace with Georgia seems far off, and the refugee problem continues to hang over the country. The Olympics could have brought Abkhazia tourists, money, and fame. But the border with Russia was sealed during the Games, leaving Abkhazia more isolated than ever.

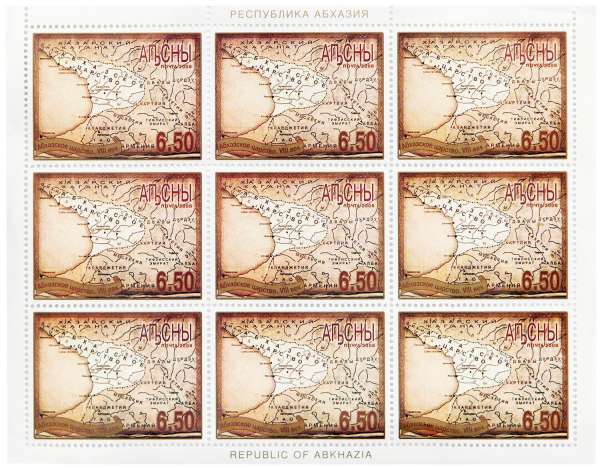

Abkhazian stamps, though Abkhazia has been cut off from the international postal system since 1991.

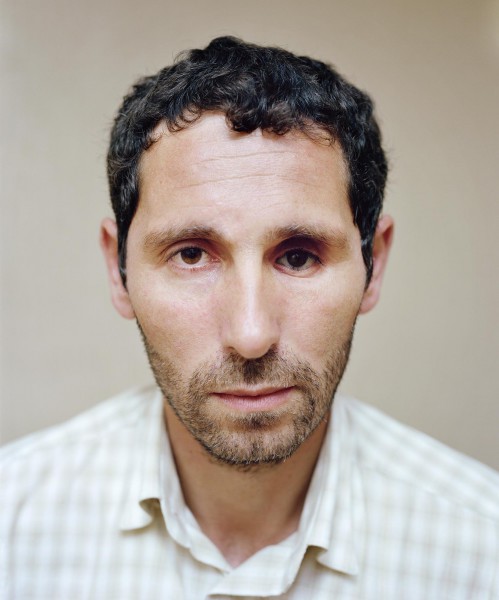

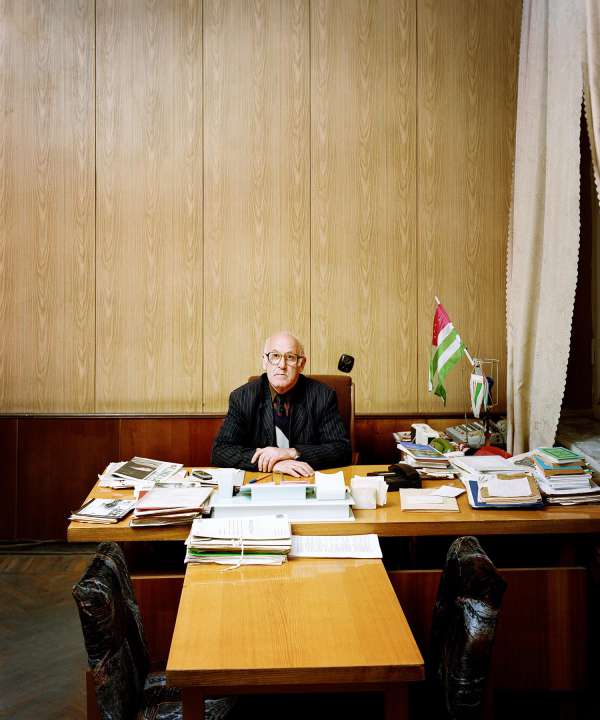

Director of the Abkhazian Post Eduard Piliya in 2009.

“You can’t stick Abkhazian stamps on your card abroad.”

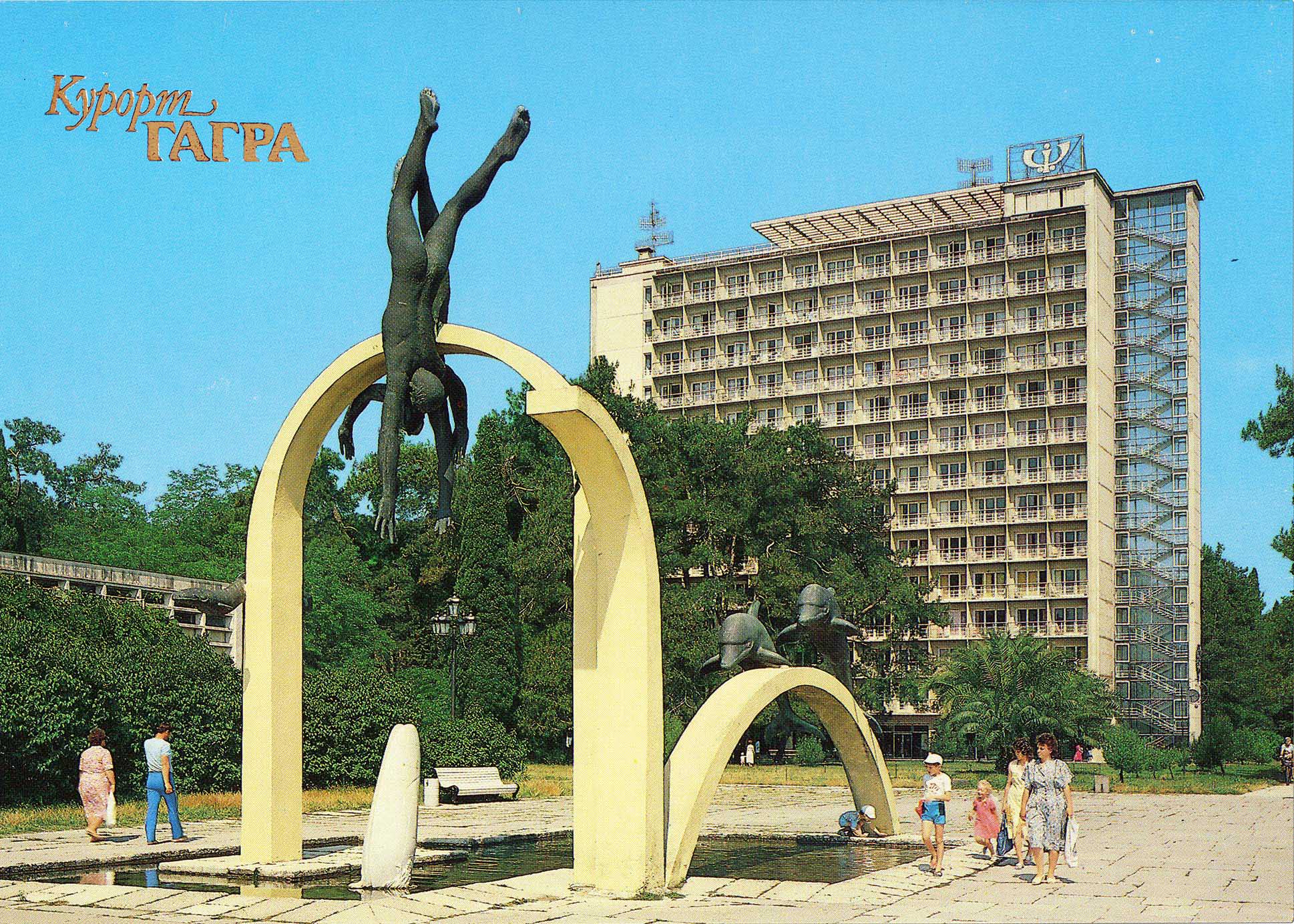

Soviet postcard and remake from tourist resort Pitsunda.

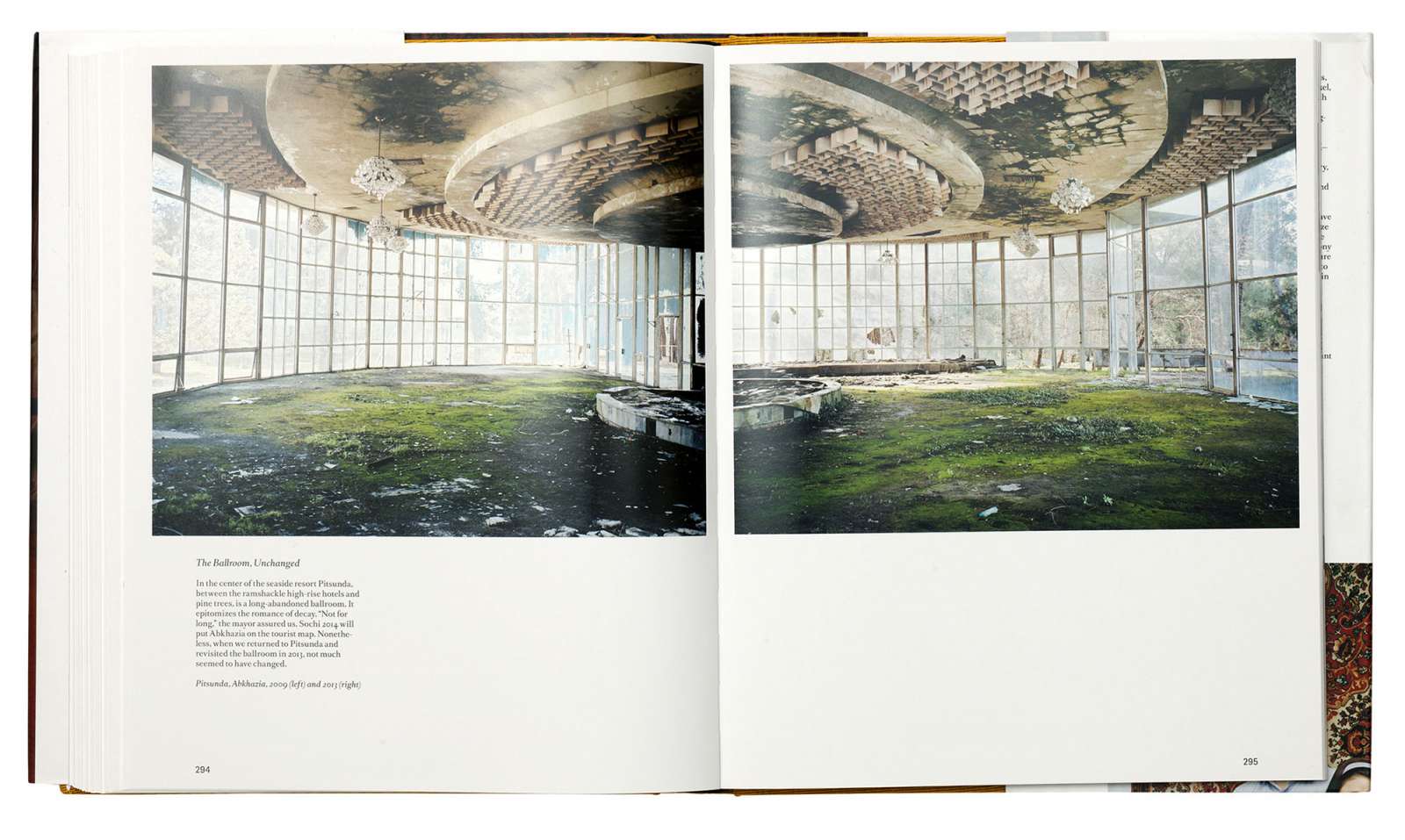

Former ballroom in seaside resort Pitsunda, 2009.

Former ballroom in seaside resort Pitsunda, 2013.

Empty, abandoned house in Sukhum, 2010.

“I’ll show you what our countryside looks like. Life may not be as luxurious as it is in the city, but we have everything we need and we know how to celebrate that.”

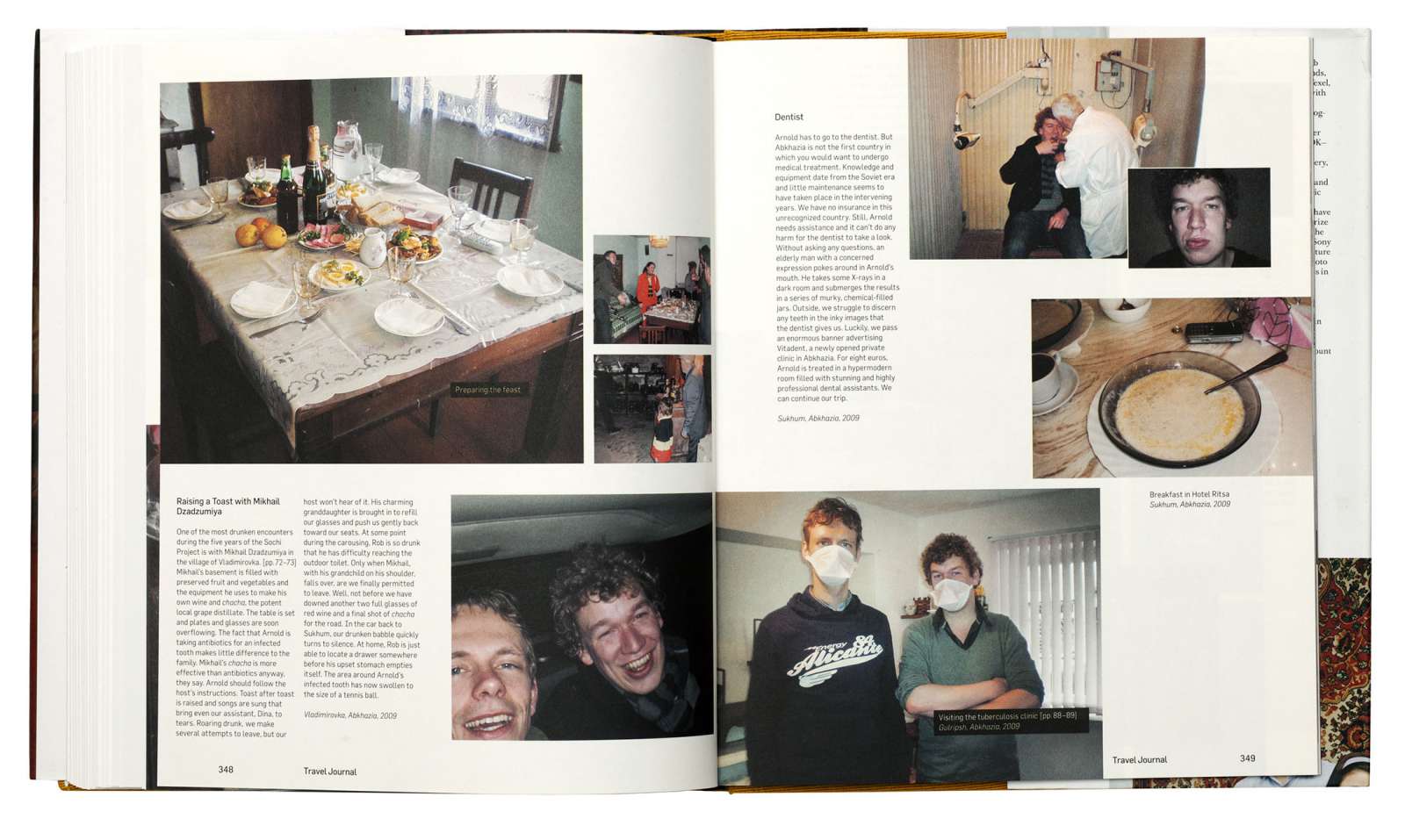

Mikhail Dzadzumiya start singing the Soviet song “Heart”, which was shot in Abkhazia.

Mikhail Dzadzumiya with daughter Natasha and friend Valentina, 2009.

Cultural center in Sukhum displays a tribute to war casualties, 2009.

“Most people in the Caucasus don’t know that democracy doesn’t mean you can do just anything at the expense of others.”

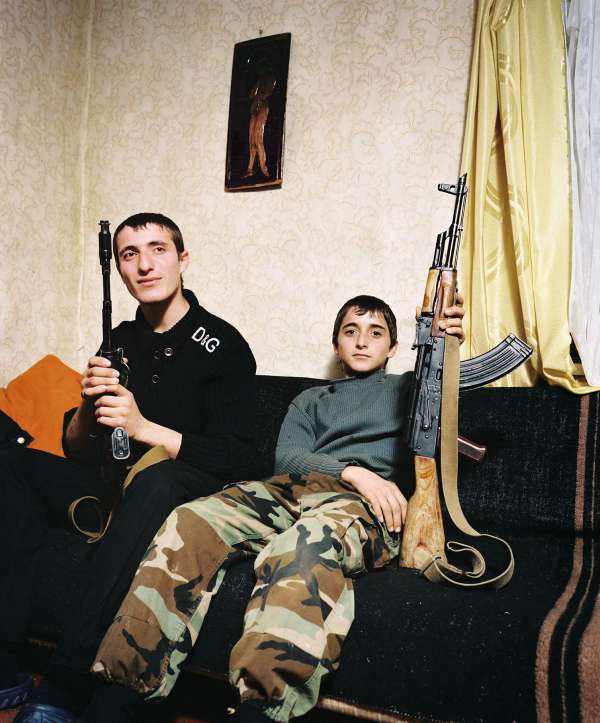

Brothers in Abkhazian mountain village Kuabchara, 2009.

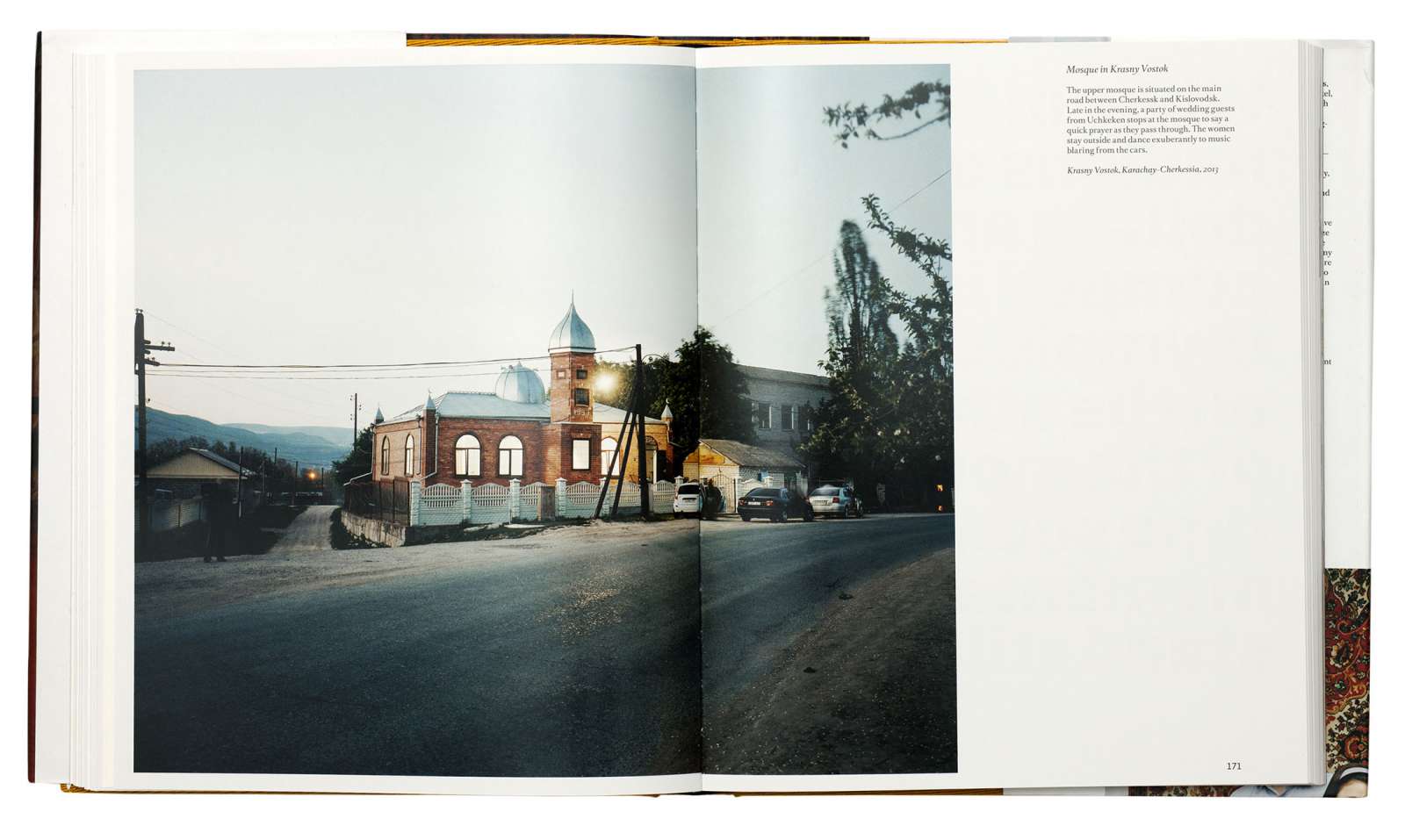

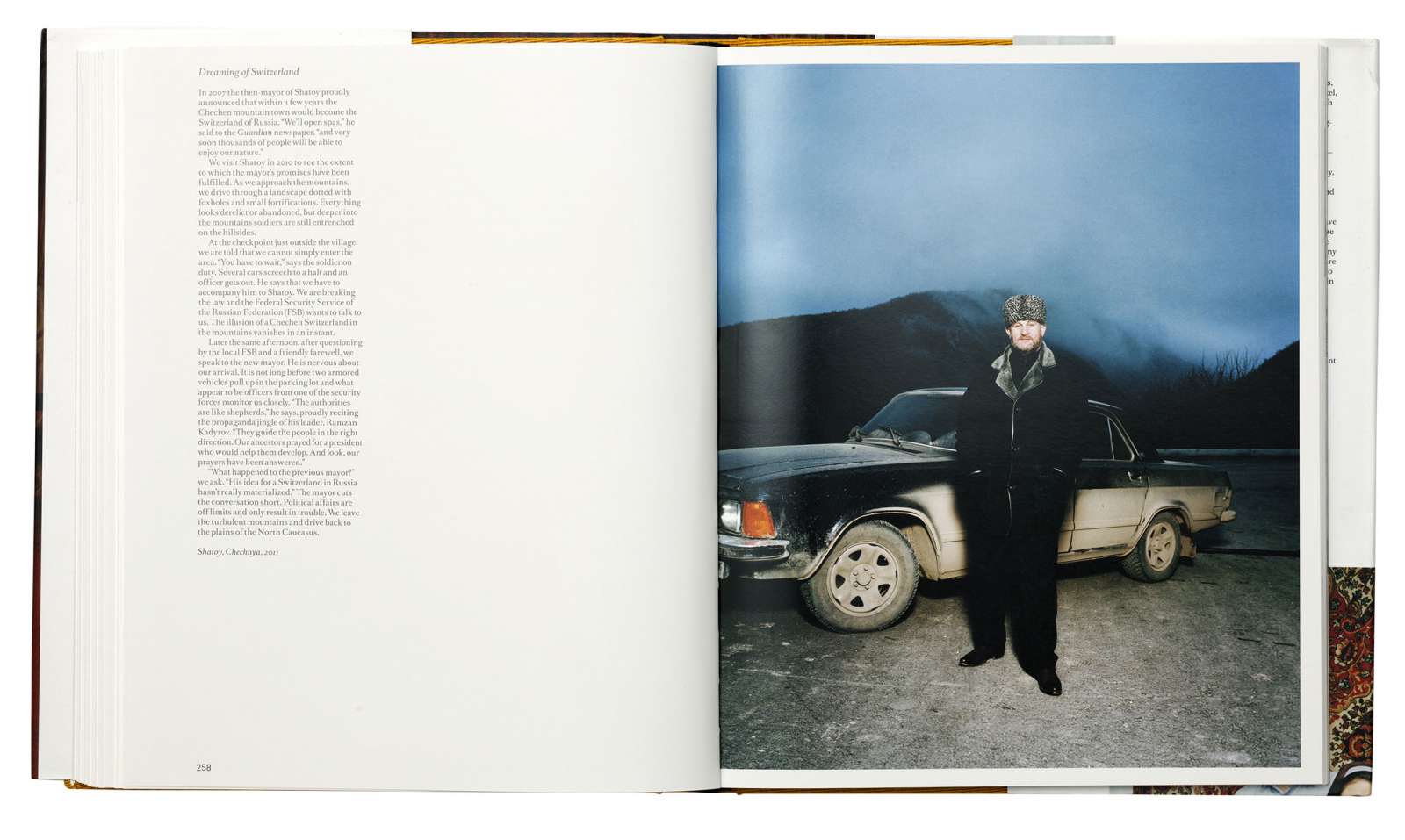

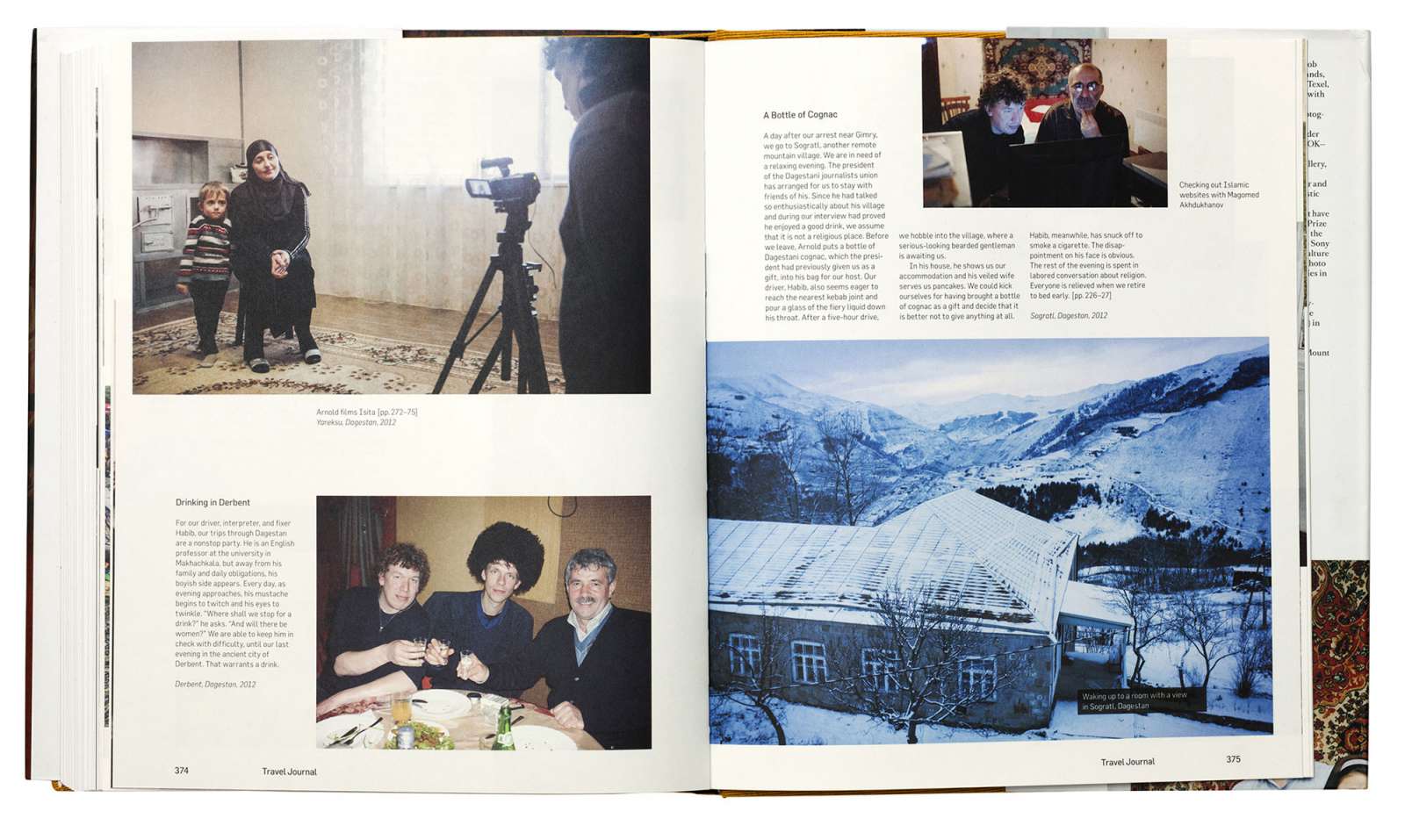

North Caucasus

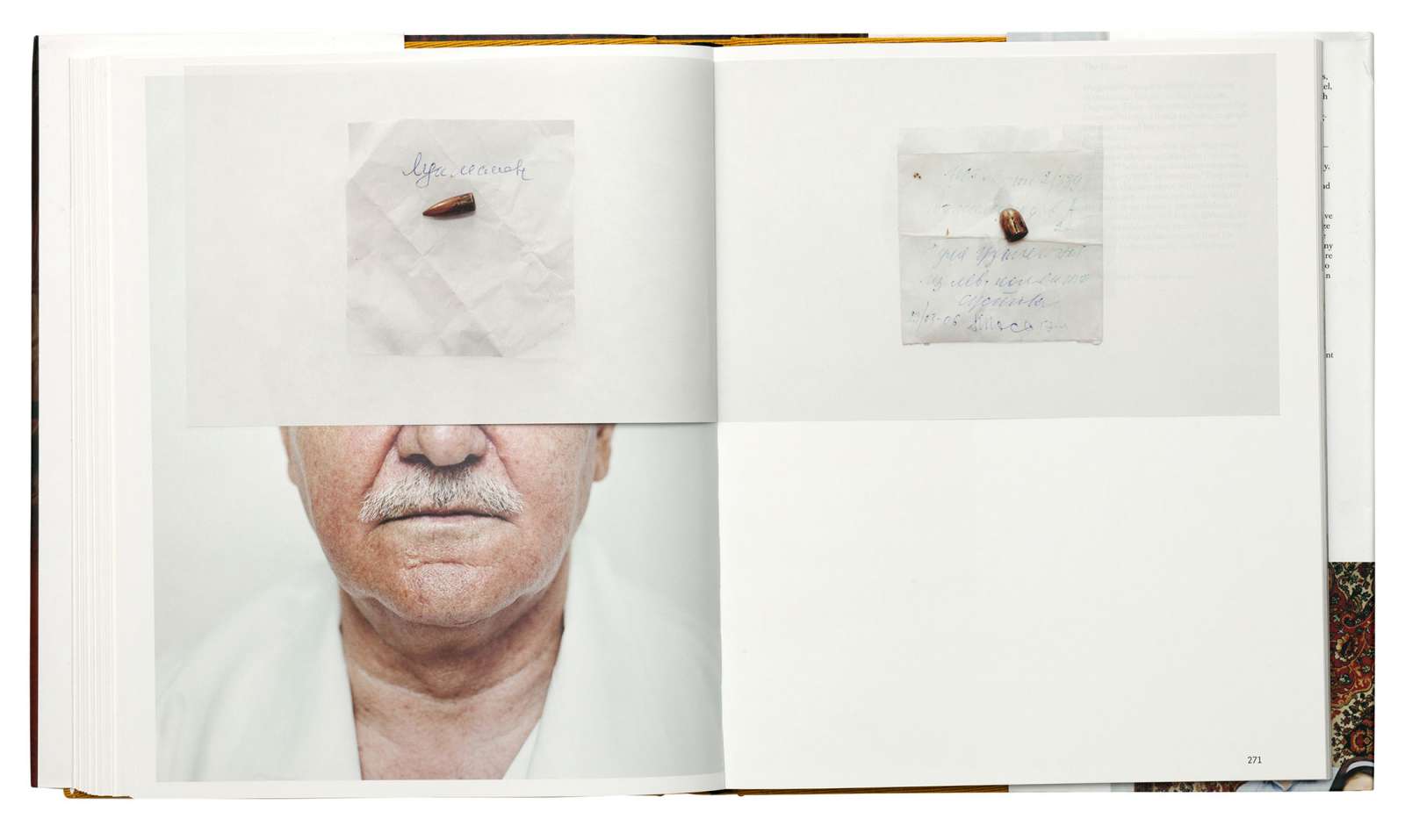

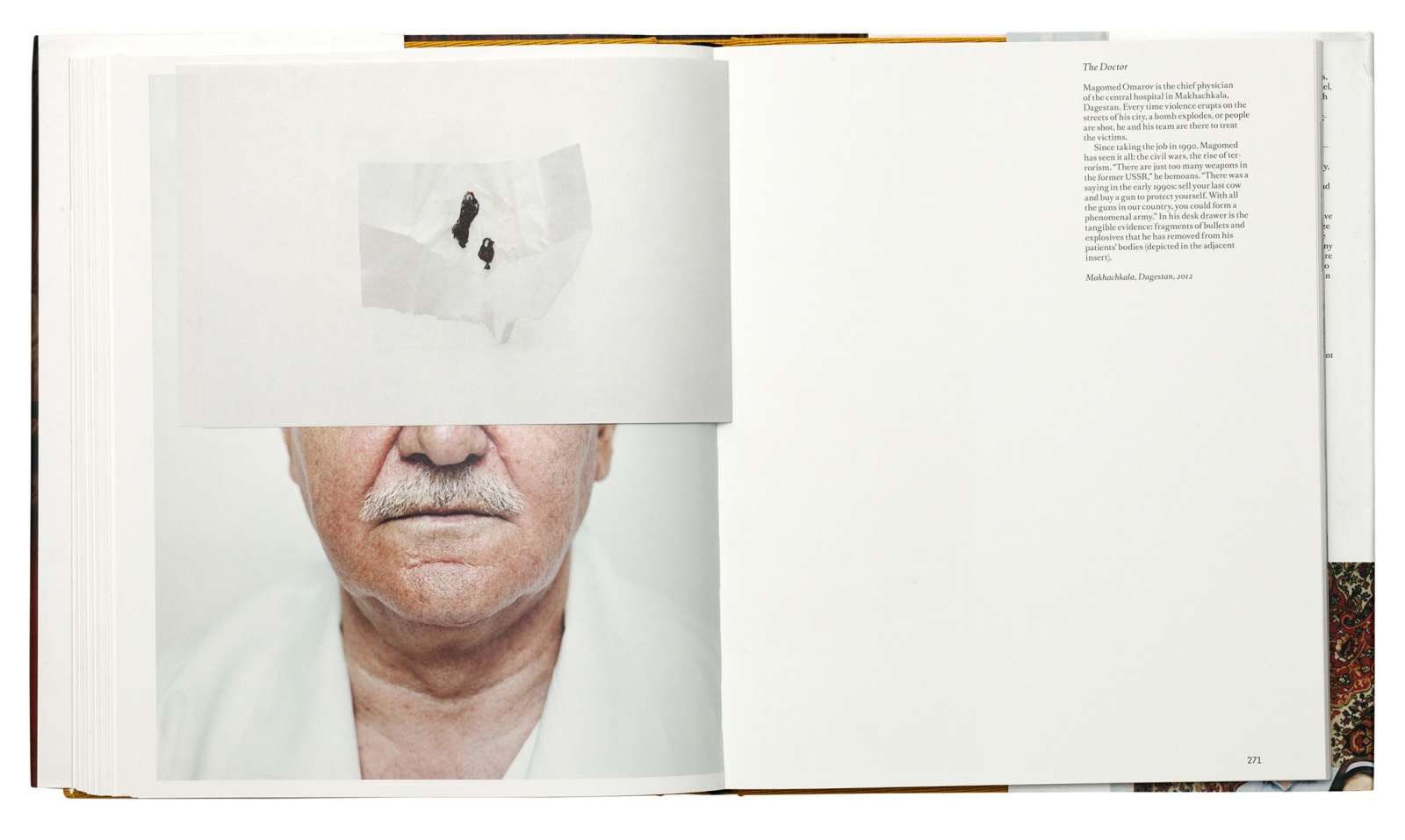

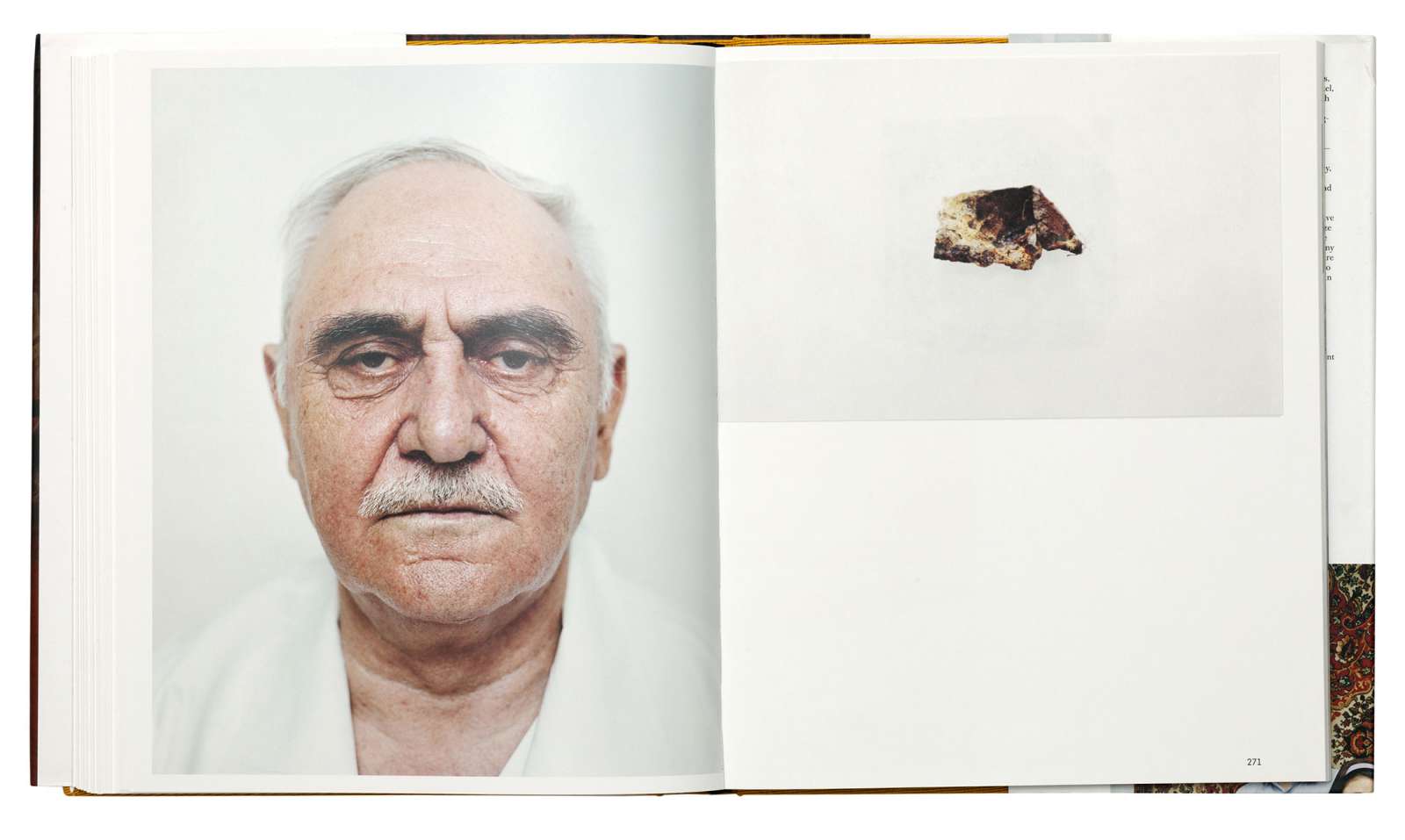

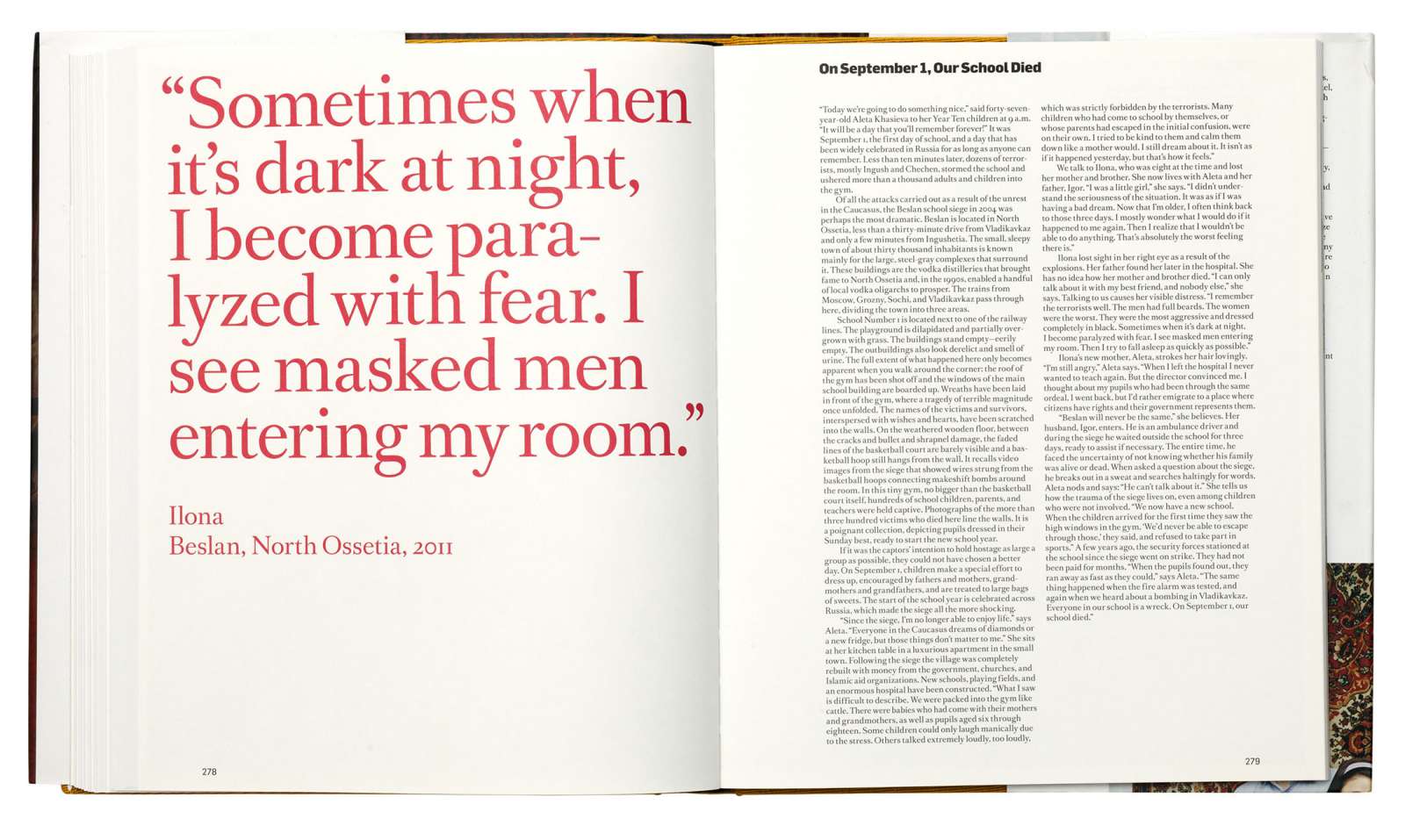

On the other side of the mountains from Sochi is the North Caucasus, the poorest and most violent part of the Russian Federation. Russia has tried to subdue the North Caucasus for 300 years. Between 1817 and 1864, it fought the Caucasian Wars that led to definitive colonization of the area. Stalin deported five ethnic groups to Central Asia and populated the region with “friendly peoples.” Immediately after the fall of the Soviet Union, war and terror ignited the region again. After Russia’s victory in the Second Chechen War, separatists withdrew into the forests and mountains, from where they orchestrated all the major terrorist attacks that have plagued Russia in recent decades. The region was the Olympic organizers’ worst nightmare: would they succeed in keeping attacks at bay? In the run-up to the Games, local rulers were given carte blanche to restore order. They failed. Instead, the number of cases of human rights abuses in the North Caucasus submitted to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has soared.

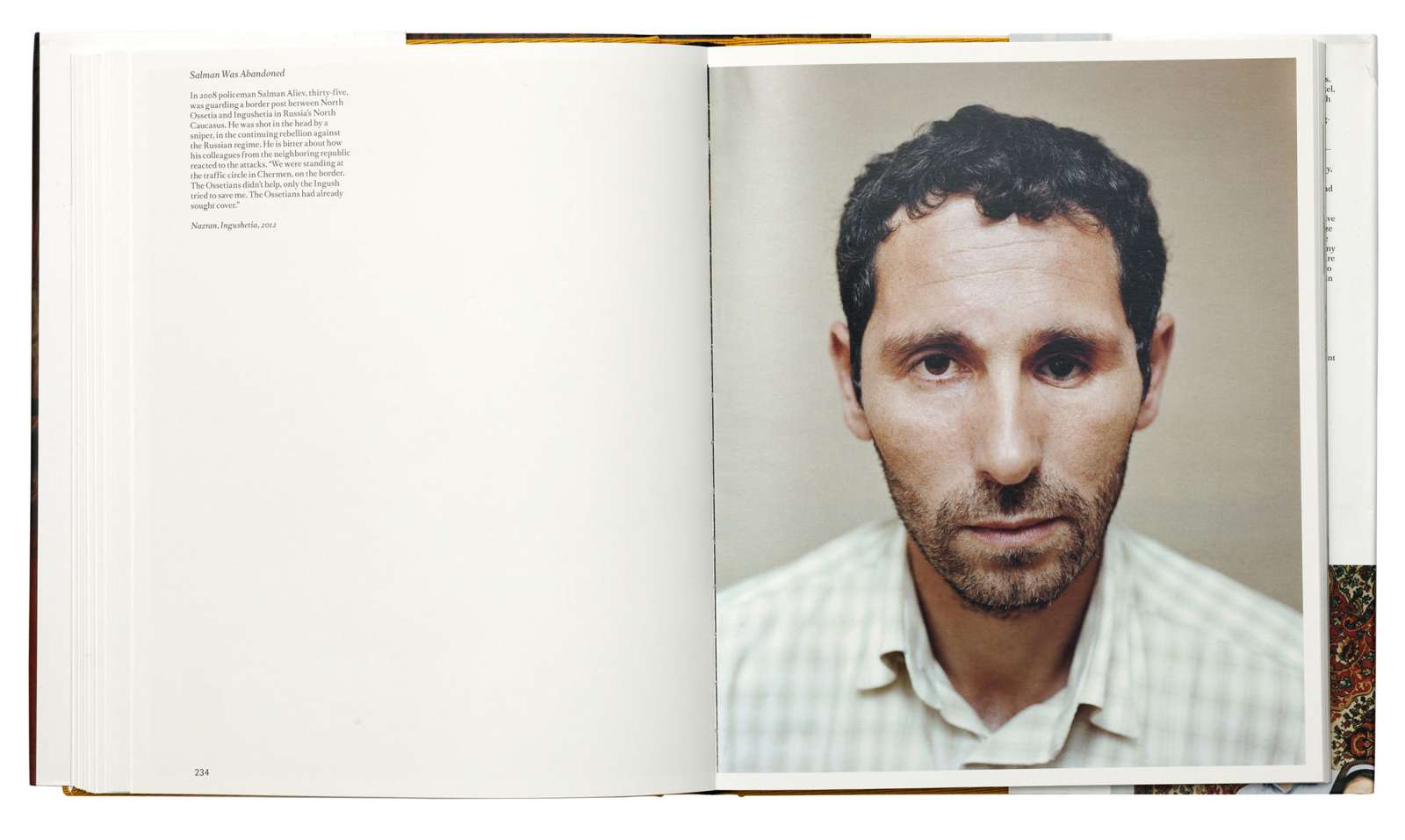

“Recently, a couple of officers were shot down by someone passing on a bike. We never practiced that scenario.”

Policeman Salman Aliev from Nazran, 2012.

Ingushetian policeman Hamzad Ivloev, 2012.

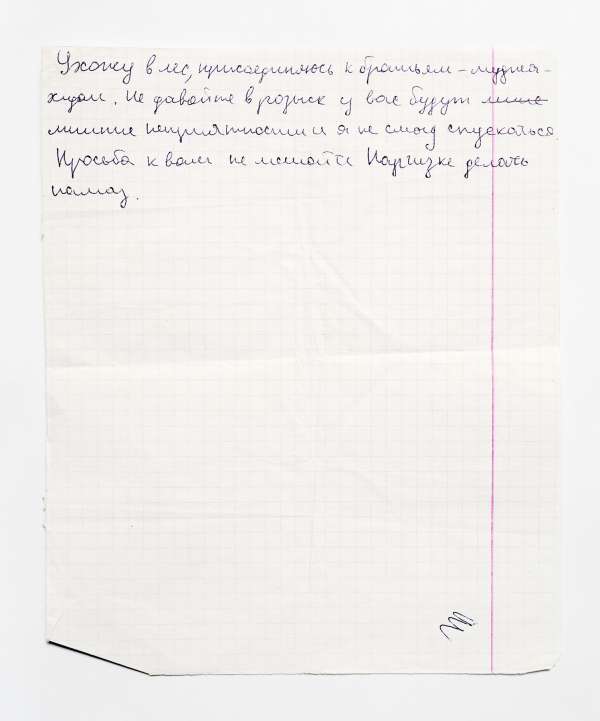

“I’m going into the woods. I’m joining the Mujahedeen brothers. Don’t register me as missing; it will only result in unnecessary unpleasantness for you. I can’t come back. I ask you not to stop [my sister] Nargiz from saying her prayers.”

Fifth time in two years that his liquor store has been blown up, 2012.

Security camera caught a bomb attack on the liquor store in Ordzhonikidzevskaya, Dagestan.

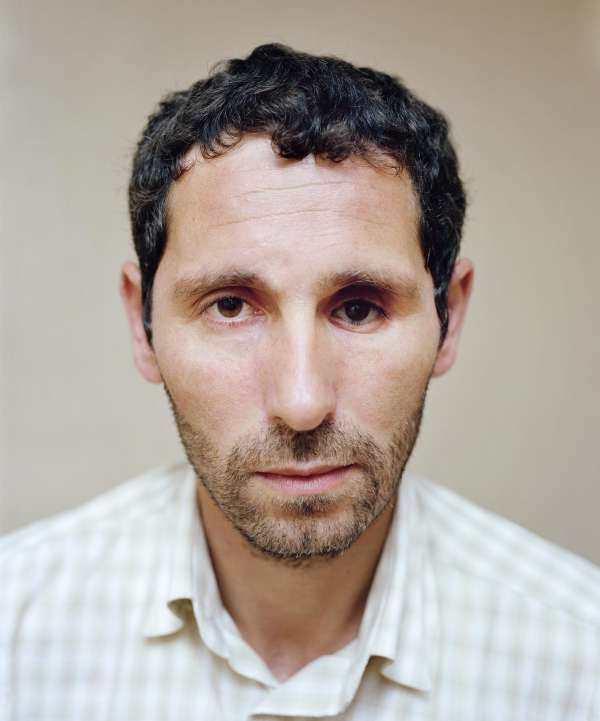

Saidachmed Nasibov was shot dead in 2012.

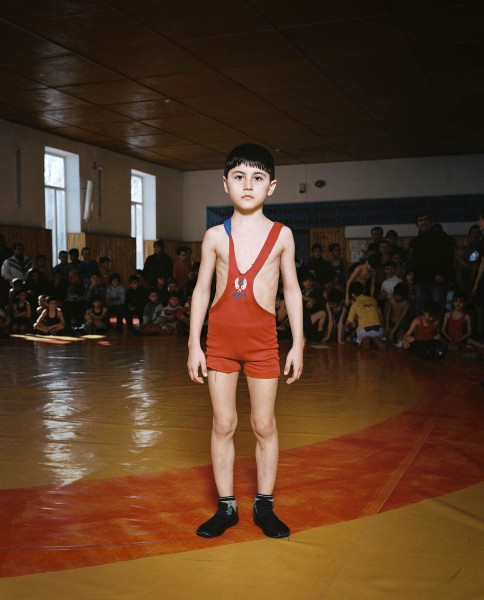

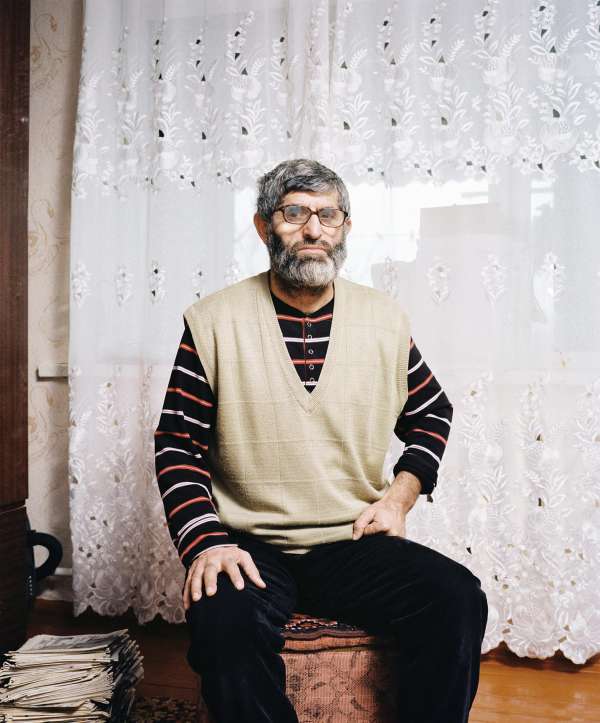

Wrestling trophy from one of Nasibov’s sons, all killed before him.

“If I were young and naïve, and unaware of the consequences, I would join the militants in the woods.”

“Human rights are actually very well defined here. But that’s on paper. As soon as you run into a uniform and a gun, it’s over.”

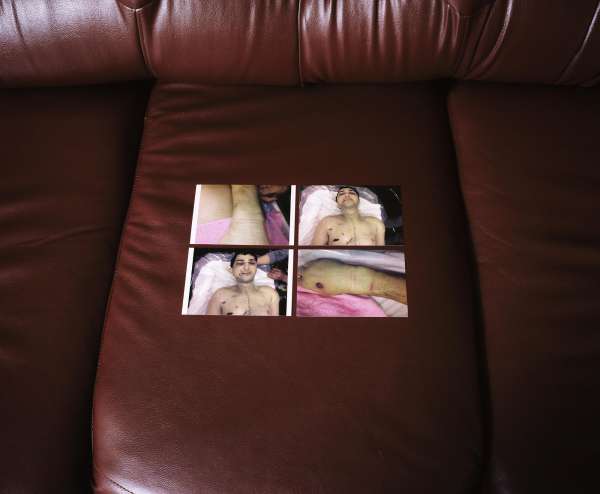

Aslan was tortured to death by security forces while being interrogated, 2012.

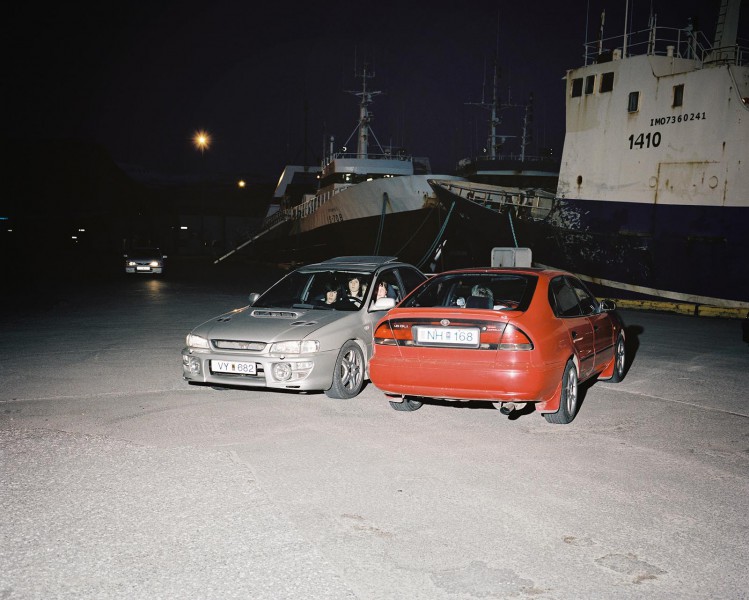

In one of the few pubs in Grozny where beer is served we watch the waitress dancing, 2011.